|

|

| |

|

| |

| Introduction to English Literature(2020-1) |

| |

|

|

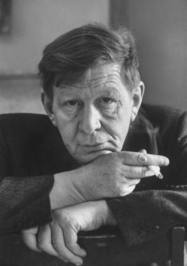

W.H. Auden(1907-1973)

W.H. Auden is widely regarded as the most important English poet of the past one hundred years. Writing in the Financial Times, Michael Glover has commented on 'the rise and rise of Auden's reputation until he is now considered one of the greatest -- if not the very greatest -- English poets of the 20th century'. Originally labelled a 'thirties poet', along with Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis, Auden is now seen as the representative twentieth-century artist and intellectual: his struggles with Freud, Marx, God and sexuality seem to epitomise and define his age. Originally infatuated with Pound and Eliot, he soon outgrew the esoteric tendencies of modernism, embracing the European poetic heritage in its entirety and experimenting with ballads, sonnets, epitaphs, odes, music hall ditties, folk songs and blues rhythms. Like Yeats, he believed passionately in reinvention and rediscovery, calling himself a 'traveller' on the 'journey of life', and constantly ditching poetic forms and registers as soon as he had mastered them. However, a recognisably 'Audenesque' voice is present in all of his best work: 'Lay your sleeping head, my love', 'As I walked out one evening', 'Musée des Beaux Arts', 'In Memory of W.B. Yeats' and 'The Fall of Rome'. This voice is intimate and bossy, earnest and funny, elegaic and impassive. Above all, its control of language is absolute. Auden's ability to choose phrases that are both appropriate and surprising remains the most enduring aspect of his legacy.

Auden was born in 1907, the third son of George Auden, a doctor, and Constance Bicknell Auden, formerly a nurse. Their marriage was not always a happy one, as Auden recalled in 1971: 'Ma should have married a robust Italian who was very sexy, and cheated on her. She would have hated it, but it would have kept her on her toes. Pa should have married someone weaker than he and utterly devoted to him.' George Auden moved the family to Birmingham in 1908, where he became a schools medical officer, responsible for improving public health in the largest industrial city in Britain. He was respected by his colleagues and remained in this position until his retirement in 1937. 'He was the gentlest and most unselfish man I have ever met,' Auden remembered. His mother was more stern and quarrelsome: a 'solemn, intense woman', according to Christopher Isherwood, whom Auden nevertheless adored.

Auden's parents influenced him in several ways. For a start, his father's medical background instilled in Auden a love of scientific enquiry that he never lost. As an adult, he would read books by archaeologists and psychologists as frequently as he would read books by poets and philosophers. His most famous poems are cold, clinical examinations of private and public illness. He found it so easy to embrace Freudian psychoanalysis in the 1920s and 1930s because he was already used to thinking in terms of sickness and cure. At the same time, his mother took control of his spiritual education. She brought him up as an Anglo-Catholic, insisting on family prayers before breakfast, and 'on Sundays there were services with music, candles, and incense' (as Auden remembered). Although he would lose his faith as an adolescent, this 'conviction that life is ruled by mysterious forces' would never leave him, and he would reconvert to Anglo-Catholicism in his mid-thirties. His mother also encouraged him to read and to appreciate music. When Auden was a boy, she introduced him to Tristan and Isolde , and mother and son would sing Wagnerian love duets to each other in the front room.

More generally, Auden would mythologise his mother and father and reintroduce them as symbols in his poetry. 'What is the use of pretending one can treat the members of one's own family as ordinary human beings?' he asked in 1963. A dominant mother would be the most dynamic feature of his first long poem, Paid on Both Sides. His play The Ascent of F6 was a study of Oedipal longings, and a grotesquely vengeful mother dominates the play The Dog Beneath the Skin. Similarly, father figures cast long shadows over The Orators and The Sea and the Mirror. Auden's habit of turning his parents into archetypes developed further after he discovered Freud and Jung in his early teens.

The other crucial event in Auden's early life was the First World War. It began when he was seven years old, and ended when he was eleven, dominating his childhood. In his early poetry, it is as if the war still continues: he is obsessed with soldiers and spies, vendettas and battles. More than any other poet of the 1930s, he lived in fear of the next war, convinced that the nations of Europe were destined to fight again. The first lines of his early poems reveal his preoccupation with military strategy: 'Control of the passes was, he saw, the key', 'We made all possible preparations', 'Pick a quarrel, go to war'. The First World War also left him with a lifelong fascination with heroism and sacrifice. Similarly, Auden became convinced that he would face a 'test' of his own, and glorified the idea of quests and missions.

In 1915 Auden was sent to boarding school at St Edmund's in Hindhead, and in 1920 he went on to Gresham's School in Norfolk. Looking back, Auden reflected: 'My political education began at the age of seven when I was sent to a boarding school. Every English boy of the middle class spends five years as a member of a primitive tribe ruled by benevolent or malignant demons, and then another five years as a citizen of a totalitarian state.' He remembered the teachers: 'Those who deep in the country at a safe distance from parents spend their lives teaching little boys, behave in a way which would get them locked up in ordinary society. When I read in a history book of King John gnawing the rush-mat in his rage, it did not surprise me in the least: that was just how masters behaved.'

However, at St Edmund's School, Auden made one of the most important friendships of his life: he met Christopher Isherwood. Although Isherwood was two years older than Auden, their shared sense of humour and passion for literature made them close acquaintances. At first Auden was determined to become a mining engineer 'and his playbox was full of thick scientific books on geology and metals and machines, borrowed from his father's library', as Isherwood remembered. However, during a walk with another friend, George Medley, in 1922, Auden was asked if he ever wrote poetry. From that moment, Auden single-mindedly devoted himself to verse and language, and began to write poems in the style of Wordsworth, Hardy and Walter de la Mare .

In 1925, Auden arrived at Christ Church College, Oxford, where he would stay for three years. He began as a student in natural science, then switched to Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE), then a few months later switched again to English. While at Oxford, he happened to meet Christopher Isherwood again and the two men began a long sexual relationship that lasted, on and off, until 1939. By this stage, Auden knew that he was a homosexual and began to write cryptic hints and allusions into his poetry. He also began to take Isherwood 's advice on which of his poems to keep and which to scrap. If Isherwood liked a single line from one poem, Auden would keep the line, often assembling entire poems in this fashion. This partly explains the fragmented, condensed, oblique nature of Auden's undergraduate verse.

Auden's time at Oxford has become mythologised by many of his contemporaries: Spender, MacNeice , Day-Lewis, Isherwood and others. He was ferociously well read and astonishingly precocious. By the age of twenty, he was co-editing a collection of Oxford Poetry. His tutor Nevill Coghill remembered: 'He had great intellectual prestige in the University at large.' Coghill also recalled: 'His sayings were widely misquoted and would appear, in their garbled form, in the essays of my other pupils. These being cross-examined, and their nonsense laid bare, still held the trump, which they would play when nothing else would save them: "Well, anyhow, that's what Wystan says".'

At Oxford, Auden also discovered Anglo-Saxon verse, a compulsory part of the syllabus that most students loathed but which Auden adored. His father had brought him up on Icelandic myths, and Auden often referred proudly to his 'Nordic' ancestors. Anglo-Saxon poetry would be a lifelong passion; Auden loved this world of liege lords, fallen warriors, hostile landscapes and gnomic, riddling wisdom. The second edition of his Poems (1933) contains a translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem, 'The Wanderer'. The early poem 'Control of the Passes' includes a quotation from 'Wulf and Eadwacer' and The Orators contains an extract from The Battle of Maldon.

The other major poetic influence on the young Auden was T.S. Eliot. He told Nevill Coghill: 'I've been reading Eliot. I now see the way I want to write.' For a while, his poetry was full of 'gasworks and dried tubers' (as he put it in 'Letter to Lord Byron') but later he came to disparage his Eliot phase as an artistic dead end. Certainly, he only found his voice when he shed Eliot 's disillusioned tone and replaced it with one of wariness and vigilance. Eliot believed in concentration, whittling down his poetry until he was left with 'a heap of broken images'. Auden would stress profusion and amplitude, trying out every conceivable poetic voice, compulsively dramatising each of his intellectual phases and moods.

After leaving Oxford, Auden spent nine months in Berlin with Isherwood and Spender. He preferred the austerity of the German capital to the clichéd aestheticism of Paris: for him Paris was 'the city of the Naughty Spree [. . .], bedroom mirrors and bidets, lingerie and adultery, the sniggers of schoolboys and grubby old men'. In Berlin he met John Layard, a disciple of Homer Lane, who introduced the poet to another batch of psychoanalytic theories. Essentially, Layard believed in acting on instinct, reversing guilt by turning its negative force into positive energy. Auden wrote in his journal: 'To cure a disease, encourage it, don't repress . . . Use love, not fear.' These ideas found their way into early poems like: 'Sir, no man's enemy, forgiving all' and The Orators . Auden fell out with Layard after the latter stole one of his boyfriends. Auden was furious with Layard: 'Tried to persuade him to kill himself', Auden wrote in his journal for 3rd April 1929. Layard duly went off and shot himself, missing his brain but putting a hole in his forehead. He then went round to Auden's house, delirious and bleeding, and asked the poet to finish him off. According to Layard, Auden said: 'I can't do it, because I might be hanged if I did. And I don't want to be.' However, on the whole, Layard was a positive influence on Auden who liberated him from feelings of guilt and encouraged him to embrace homosexual promiscuity. The two men maintained a loose acquaintanceship that lasted until the Second World War.

In July 1929, Auden returned to England. He had been briefly engaged to a nurse called Sheilah Richardson, but after his experiences in Berlin he broke this off immediately, writing in his journal: 'Never -- Never -- Never again.' He later told Naomi Mitchison that heterosexuality was 'like watching a game of cricket for the first time': 'I am not disgusted but sincerely puzzled at what the attraction is.' In April 1930 he secured a post as a teacher at Larchfield Academy, a boy's school in Scotland. Between 1932 and 1935, he was a teacher at the Downs School in the West Midlands.

During this period, Auden was establishing a reputation as the most promising young poet of his generation. In 1928, Stephen Spender had used a hand-press to publish twenty of Auden's 'Oxford' poems, several of which had attracted critical attention. In particular, 'The Watershed' seemed to represent a new kind of poetry, brilliantly tuned into the fears and hopes of the inter-war generation. The run-down industrial landscape of Auden's youth in the Midlands is turned into a general metaphor for the moral and social decline of Britain, the compressed and chilly diction emphasising the sense of isolation and fragmentation. Written when he was twenty, 'The Watershed' was Auden's first wholly successful poem, his first attempt to link private and public neuroses, his first successful synthesis of his psycho-analytic theories of free association and his modernist principles of clinical economy and linguistic collage.

But Auden's first public success came in 1930 when T.S. Eliot at Faber & Faber agreed to publish his Poems . Eliot had originally rejected a selection of Auden's work in 1927, but by 1930, Eliot had become convinced that Auden was an important new voice ('This fellow is about the best poet I have discovered in several years'). As well as half a dozen of the poems in Spender 's hand-printed volume, Auden's 1930 collection contained many of his most impressive early pieces, including 'Paid on Both Sides', 'It was Easter as I walked in the public gardens' and 'Consider this and in our time'.

'Paid on Both Sides' is a dramatic 'charade' about an obscure feud between bitter rivals in an unspecified country. At the beginning of the play, John Nower is planning to kill Red Shaw as an act of vengeance. Years before, Red Shaw killed Nower's father. After ambushing Shaw and murdering him, Nower marries Shaw's sister as a way of bringing peace to the country. However, Shaw's brother, Seth, is ordered by his mother to kill Nower on his wedding day. Nower is murdered and the feud continues.

At the same time, there are a host of secondary characters that demonstrate Auden's love of farce and music hall routines. A spy is tried by Father Christmas. A doctor appears to examine the spy and brings an impertinent servant with him. Rather than alleviating the atmosphere of doom and menace, these comic interludes only add to it, hinting at an underlying anarchy and lawlessness.

The rest of the poems in the collection share the same doom-laden, cold, forbidding landscape. Medical and military metaphors converge as Auden dissects a country that is either recovering from or entering into war. Where human communication occurs, it is in code, dense and difficult. The poet observes what is happening from a 'hawk's vision': he looks down like a general planning troop movements on a map, or a doctor looking down at T.S. Eliot 's 'patient etherized upon a table'. He is a 'tiny observer of enormous world', mimicking the 'hawk's vertical stooping from the sky'. His tendency is to generalise and to preach, but also to draw back from human contact.

Auden returns to the same concerns and pre-occupations in his next major work, The Orators (1931), a long, complex, multi-faceted poem which has the capacity to both confuse and enchant. The title is appropriate because the poem is essentially an excuse for Auden to try out different voices: he writes pastiches of rhetorical speeches, prayers, riddles, letters, dreams, journals, fairy tales and elegies. The poem begins with a Headmaster asking his pupils: 'What do you think about England, this country of ours where nobody is well?' The country is turned into a patient suffering from a psychological malaise. This idea is underlined in the section entitled 'Letter to A Wound,' in which a love letter sent by a patient to his mystery illness allows Auden to meditate on the curious appeal of pain and sickness.

The second section introduces the possibility of a hero to cure the ills of the nation. Auden told Eliot that: 'the central theme is a revolutionary hero.' In this way, The Orators is Auden's first real study of a potential political and spiritual saviour, a subject that he would return to in plays like The Ascent of F6. The hero in this case is a young aviator. His journal is full of information about fellow pilots and possible enemies, for example, 'Three kinds of enemy walk -- the grandiose stunt -- the melancholic stagger -- the paranoic sidle'. However, as the journal proceeds, it becomes apparent that the aviator is also psychologically ill, plagued by doubts and neuroses. He is especially haunted by the figure of an Uncle, his 'real ancestor' who inspired him to be a pilot.

The third section of the poem consists of a series of odes to Auden's friends. They are a combination of private jokes and public observations about Britain's sickness.

Five years after The Orators, Auden published his next major collection, Look, Stranger! (1936) (published in the United States the following year as On this Island). In this collection, although still fond of abstract and cryptic generalisations, he also began to associate writing with public duty, and consciously coined aphorisms that might sum up the moods and anxieties of Britain as a whole. In a sense, his ideological allegiance had shifted from Freud to Marx, and he began to treat 'neuroses' and 'repression' as political problems. At the same time, his more private and intimate poems dispensed with the paranoid encryption that was such a feature of his earlier work. Cautiously and gradually, Auden began to admit his need for love and his faith in friendship.

The most stirring public pronouncement in the volume is probably the title poem, which begins:

Look, stranger, at this island now

The leaping light for your delight discovers,

Stand stable here

And silent be,

That through the channels of the ear

May wander like a river

The swaying sound of the sea.

This represents a turning point in Auden's career: for the first time, he was identifying both with the British public and with the 'stranger'; he was looking at his country as an insider and an outsider simultaneously.

Auden also began to write more intimate poems like 'Out on the lawn I lie in bed' which is a hymn to friendship, a celebration of a truly happy and unrepeatable period of companionship:

Equal with colleagues in a ring

I sit on each calm evening,

Enchanted as the flowers

The opening light draws out of hiding

From leaves with all its dove-like pleading

Its logic and its powers.

The collection also contains more mature formulations of Auden's earlier preoccupations, such as a sonnet about heroism, loosely based on Lawrence of Arabia and sometimes known as 'Who's Who'.

In 1935, Auden gave up teaching and spent four years leading a somewhat nomadic existence. Between 1927 and 1935 he seemed to be on an intellectual quest, reading Freud , Marx and T.S. Eliot. After 1935 this became a geographical quest, and he visited Spain, Iceland and China, and finally moved permanently to the United States in 1939.

The last few months of 1935 were spent working on a documentary for the Post Office. The lines he provided for Night Mail would become some of the most famous in his oeuvre:

This is the night mail crossing the border,

Bringing the cheque and the postal order,

Letters for the rich, letters for the poor,

The shop at the corner and the girl next door.

In June 1935 Auden married the German Erika Mann, in order to provide her with a British passport and an escape from the Nazis ('What are buggers for?' he commented). In 1936 he spent the summer in Iceland with Louis MacNeice, producing the collaborative collection, Letters from Iceland ; in 1937 he drove ambulances for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, writing the poem 'Spain 1937' shortly afterwards; in 1938, he went to China with Isherwood, after Faber commissioned a travel book on the war in the Far East, and in summer 1938 he visited New York for the first time.

Letters from Iceland (1936), written with Louis MacNeice, is one of the best-loved collections of British poetry of the twentieth century. Written in a holiday spirit, it contains a mixture of great poetry and forgettable whimsy and survives as a testimony to the close friendship of these two formidable writers. Both poets produced some of their finest work ( MacNeice 's 'Postscript to Iceland' and Auden's 'Journey to Iceland' and 'Letter to Lord Byron'). For Auden in particular, exploring his Nordic roots was an almost mythic experience.

'Letter to Lord Byron,' probably Auden's greatest long poem, sits at the centre of the volume showing just how far Auden had progressed from the gnomic, stunted verse of 'The Watershed'. The poem consists of a series of witty and insightful observations about the state of Britain and the condition of W.H. Auden in the summer of 1936. He praises 'novel writing' as a 'higher art than poetry; discusses his love of industrial landscapes; talks about how the world has changed since Byron's day; defends light verse and argues that poetry must be varied; dismisses nature poetry and asserts:

To me Art's subject is the human clay

And landscape but a background to a torso.

He identifies himself with society poets like Dryden , Pope and Byron . After describing his personal appearance to Byron , he goes on to explain why he feels the need for this poetic confession:

So I sit down this fine September morning

To tell my story. I've another reason.

I've lately had a confidential warning

That Isherwood is publishing next season

A book about us all.[. . .]

Isherwood 's 'revelations' were not dramatic enough to stop the two writers going to China in 1938. The book they produced contains a sonnet sequence by Auden, 'In Time of War', that is both a technical triumph and an insightful meditation on the effects of war.

Another Time, published in 1940 after Auden's move to the States, is generally regarded both as his finest single volume and one of the greatest collections of poetry in English literary history. Like Hardy 's Satires of Circumstance (1914), Hopkins 's Poems (1918) or Eliot 's The Waste Land (1922), it was a collection that seemed to change forever the way in which poetry was read and understood. It contains nearly all of Auden's greatest verse: 'Lay your sleeping head', 'As I walked out one evening', 'Musée des Beaux Arts', 'Spain 1937', 'In Memory of W.B. Yeats', 'September 1, 1939', his three ballads, 'Miss Gee', 'Victor' and 'James Honeyman', the series of poems on other writers, 'A.E. Housman', 'Matthew Arnold', 'The Novelist' and 'Edward Lear' and the series of lyrics and songs, 'O tell me the truth about love', 'Funeral Blues' and 'Refugee Blues'.

'Lay your sleeping head' is a celebration of an uneven, flawed love affair. Rather than idealise the beloved, he is 'mortal, guilty', similarly the poet is 'faithless' and their love is 'ephemeral'. Nevertheless, they have a moment together and its perfection is dependent upon an honest acknowledgement of their relationship's frailty. 'Spain, 1937' is a 'hawk's eye' view of the Spanish Civil War, placing the conflict in the context of History. Using repetition and rhetoric, Auden looks at Spain 'yesterday', 'today' and 'tomorrow'. Auden also shows how the Spanish Civil War was a different experience for each participant, young poets and writers imposing their own private conflicts onto the country. British intellectuals wrote constantly about Spain in the 1930s, and Auden's poem can usefully be compared to Orwell 's Homage to Catalonia and Section VI of Louis MacNeice 's Autumn Journal. (Indeed MacNeice later commented: 'We needed Spain more than Spain needed us.').'Musée des Beaux Arts' is a poem about suffering and indifference. Auden is looking at Old Masters in a gallery and notices a discrepancy between the suffering and ecstasy of saints and religious icons, and the inevitable impassivity of bystanders (and those who look at the paintings).

'In Memory of W.B. Yeats' is both an appreciation of the Irish poet and a summary of Auden's thoughts on poetry in January 1939. The first section focuses on Yeats 's actual death; the second is a meditation on his verse; and the third is a series of couplets on the subject of art and time:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

'September 1, 1939' is generally regarded as Auden's masterpiece, his complex reaction to the war that he always knew was coming. At the time Auden was in America, and the mixture of detachment from the European scene and complete absorption in the apocalyptic situation is what gives the poem its uniquely wise and humane tone. After noting a universal mood of anger and fear, Auden proceeds to look at the causes of the war, blending his views on history, psychology and religion, mentioning Luther, Hitler and Thucydides. At the end of the poem, Auden tries to come to terms with his feelings of powerlessness and anger. His poem becomes a defiant response to the 'international wrong'. He will ignore 'the lie of Authority' and the falsifications of History and place his trust in humanity: 'We must love one another or die.' In the face of World War, Auden advises a limited, cautious amount of hope. He is 'beleaguered by the same / Negation and despair' but he will 'show an affirming flame'.

By 1940, Auden and Isherwood had moved to the United States permanently. This caused a huge amount of resentment in Britain; they were depicted as 'deserters' who had abandoned their country in its hour of need. Evelyn Waugh portrayed them as 'Parsnip and Pimpernel', two camp and pretentious cowards, in his 1942 novel Put Out More Flags. Reviewing Spender 's memoirs in 1951, Waugh also accused Auden of fleeing to the States 'at the first squeak of an air raid warning'. However, Auden was no coward: he had been involved in wars in China and Spain and in 1942 he was happy to appear before the US military draft board. He was turned down by the army on the grounds of his homosexuality.

Two other incidents transformed Auden's life in America. He met Chester Kallman and he reconverted to Anglo-Catholicism. Kallman was 18 when he met Auden at a poetry reading in 1939. Kallman had always intended to flirt with the poet, telling his friend before the reading: 'Did you know that Auden and Isherwood are reading on West Fifty-Second Street next week? Let's sit in the front row and wink at them!' However, this casual affair would turn into the most enduring and meaningful relationship of Auden's life. For Auden, he and Kallman were like husband and wife: he wrote to his brother John in May 1939, 'it's really happened at last after all these years. Mr Right has come into my life [. . .]. This time, my dear, I really believe it's marriage.' Auden and Kallman had much in common, including a love of psychoanalysis and self-dramatisation that frequently led to heated exchanges, such as this argument on a train in 1940. 'Passengers stared in disbelief' as Auden and Kallman screamed:

WYSTAN: I am not your father, I'm your mother .

CHESTER: You're not my mother! I'm your mother!

WYSTAN: No, you've got it all wrong. I'm your mother!

CHESTER: You're not. You're my father .

WYSTAN: But you've got a father. I'm your bloody mother and that's that, darling! You've been looking for a mother since the age of four!

CHESTER: And you've been obsessed with your mother from the womb! You've been trying to get back ever since, so I am your mother! And you're my father!

WYSTAN: No, you want to replace your father for marrying women who rejected you, for which you can't forgive him. But you want a mother who will accept you unconditionally as I do...

CHESTER: I'm your goddamn mother for the same reason.

The most painful event of Auden's life took place in 1940 when he realised that Kallman had been unfaithful to him and always would be unfaithful. Their tortuous but lifelong relationship inspired some of Auden's most moving and troubled later poetry.

In America, Auden also rediscovered God. In November 1939, he went to a German-language cinema that was showing a Nazi propaganda film before the main feature. Auden was appalled when German audience members reacted to the appearance of Poles and Slavs on the screen by screaming: 'Kill them!' This sudden encounter with 'the evil incarnated in Hitler' inspired Auden to return to the Church. Christian imagery had been a feature of much of his earlier verse, like 'No man's enemy, forgiving all' and the sonnet 'Certainly praise' from In Time of War. However, by 1939, he was ready for the discipline and comfort of active faith. His Christianity became more pronounced after the death of his mother in 1941, and he wrote the Christmas Oratorio, For the Time Being (1944), in her honour. The sequence of religious poems, Horae Canonicae, would be written between 1949 and 1954. At the same time, Auden's faith was never strictly conventional. He took to referring to the deity as 'Miss God' (for example, he said of homosexuality: 'Of course it's a sin. We just have to hope that Miss God will forgive us.'). He also managed to turn much of the Bible into a psychoanalytic case study.

The poetry that Auden produced after his move to the United States provoked distinctly mixed reviews. Philip Larkin 's rhetorical question ('What's become of Wystan?') was a representative response. Auden's post-1939 work seemed to head in two directions: it was either dense philological game-playing with a religious tinge, or simplistic light verse written with a prosy casualness. It lacked the authority and energy of the '30s poetry. It seemed to turn in on itself: its subject matter was art not life. Since Auden's death in 1973, this critical consensus has been modified slightly. Although Auden's late verse is still not regarded as highly as his '30s output, many of his later lyrics, like 'The More Loving One', 'Their Lonely Betters' and 'The Fall of Rome' have been praised, as has the long poem 'The Sea and the Mirror'. Edward Mendelson's book, The Later Auden (1999), has been instrumental in resurrecting Auden's 'American' reputation.

Certainly Auden was prolific in the United States. New Year Letter, written in 1940 and published in 1941, was a long poem in octosyllabic rhyming couplets about art, war and faith, followed by eighty-one pages of prose notes. He wrote the long epithalamium 'In Sickness and in Health' in 1940; he published the elegy 'At the Grave of Henry James' in Horizon in 1941. He supplied the libretto for Benjamin Britten 's Paul Bunyan, first performed in 1941. Another long poem, For the Time Being, followed in 1944, and another, The Age of Anxiety, appeared in 1947. He began writing the sequence Horae Canonicae in 1949.

However, the greatest work of this period is probably The Sea and the Mirror (1944), a lengthy poetic response to Shakespeare 's The Tempest. Frank Kermode has described it as 'the peak of Auden's achievement'. The Tempest is an appropriate subject for Auden because after 1939 he has much in common with Prospero -- an exile whose artistic authority cannot mask his profound melancholy.

The Sea and the Mirror is a series of monologues in which all the play's characters reveal their true natures and also make more general points about the role of creativity in a fallen world. In the first section, Prospero is the poet meditating on his art; the second section is a series of poems spoken by the 'supporting cast', all of whom are undermined by refrains from the malevolent Antonio; the third section, a prose address entitled 'Caliban to the Audience', is usually described as the most successful part of the poem. This is a celebration of the vulgar and bestial in art. Caliban's humanity is compared to the audience's -- together these mortal agencies are contrasted with the 'high strangeness' and separateness of immortal art. Caliban argues that the audience wants Art and Life to be distinct. Moreover he suggests that both Art and Life are essential, to dwell permanently in either would be terrifying, to be 'released' from life into art is as vital as being 'released' back into life at the end of a play or poem. The actors too need 'that Wholly Other Life' that lies across 'an essential emphatic gulf' symbolised by 'mirror and proscenium arch'.

Other important poems of Auden's late period include 'In Praise of Limestone' (written in 1948), 'The Fall of Rome' and 'The Shield of Achilles' (both published in 1955 in the collection The Shield of Achilles ) and 'The more loving one' (published in Homage to Clio in 1960). These poems all possess the exile's melancholy and detachment. 'In Praise of Limestone' is a reflection on the English countryside that he had left behind in 1939. 'The Fall of Rome' is in many ways a recapitulation of many of Auden's '30s obsessions, since it evokes a general atmosphere of threat and menace, and hints at the imminent collapse of civilisation. The simplicity of diction in this poem is typical of the later Auden, as is his tone of impotent mourning. A comment he made in the 1950s reveals a similar mood of resignation: 'One ceases to be a child when one realizes that telling one's truth does not make it any better. Not even telling it to oneself.' 'The Shield of Achilles' is one of Auden's most widely-praised later poems. On the simplest level, it is about a shield made by Hephaestos for Thetis, but on another, it is about the duty of art to reflect sorrow and suffering, and the disappointment of readers who expect poetry to be celebratory. Like 'The Fall of Rome', 'The Shield of Achilles' is about powerlessness in the face of violence and death. But it is also about the responsibility of the artist to stand outside his age, and 'undo the folded lie'. Hephaestos has to depict the truth as he sees it, whether he wants to or not.

Another explanation for the apparent waning of Auden's reputation in America is the claim that, after 1939, he became a reader, not a writer, a critic, not a poet. Indeed, along with T.S. Eliot, he became one of the most highly respected literary critics of the twentieth century. The Dyer's Hand, published in 1963, contains some of the most influential essays of the late twentieth century: 'To get a true idea of them, one must imagine Coleridge as a man of the 1950s and 1960s', the Sunday Times commented. Forewords and Afterwords, published in 1973, is an excellent companion piece, containing Auden's collected book reviews.

The Dyer's Hand is written largely in note form, 'because as a reader, I prefer a critic's notebooks to his treatises', Auden explained. It contains some of his most important pronouncements on poetry and history. For instance, in the essay 'Reading', he declares:

As readers, most of us, to some degree, are like those urchins who pencil moustaches on the faces of girls in advertisements.

In general, when reading a scholarly critic, one profits more from his quotations than from his comments.

One cannot review a bad book without showing off.

A writer, or at least, a poet, is always being asked by people who should know better: 'Whom do you write for?' The question is, of course, a silly one, but I can give it a silly answer. Occasionally I come across a book which I feel has been written especially for me and for me only. Like a jealous lover, I don't want anybody else to hear of it. To have a million such readers, unaware of each other's existence, to be read with passion and never talked about, is the daydream, surely, of every author. In the essay, 'Writing', he comments:

Every 'original' genius, be he an artist or a scientist, has something a bit shady about him, like a gambler or a medium.

What makes it difficult for a poet not to tell lies is that, in poetry, all facts and all beliefs cease to be true or false and become interesting possibilities.

Every work of a writer should be a first step, but this will be a false step unless, whether or not he realize it at the time, it is also a further step.

The poet who writes 'free' verse is like Robinson Crusoe on his desert island: he must do all his cooking, laundry and darning for himself. In a few exceptional cases, this manly independence produces something original and impressive, but more often the result is squalor.

Poetry is not magic. In so far as poetry, or any other of the arts, can be said to have an ulterior purpose, it is, by telling the truth, to disenchant and disintoxicate.

'Making, Knowing and Judging' and 'The Virgin and the Dynamo' are good accounts of Auden's poetic evolution and his theoretical beliefs. In 'The Poet and the City', he looks at how the Industrial Revolution has changed art and society, placing particular emphasis on the transformation of technology, science and religion. He also begins to characterise poetry as a game or sport. Other essays, like 'Hic et Ille' and 'Balaam and His Ass' contain his eccentric views on selfhood, love and the division between the sacred and the profane. 'The Guilty Vicarage' is a seminal essay on detective fiction, in which he argues that the genre indulges the fantasy 'of being restored to the Garden of Eden'. In 'The I Without A Self', he attempts to analyse Kafka 's parables:

Sometimes in real life one meets a characters and thinks, "This man comes straight out of Shakespeare or Dickens ", but nobody ever met a Kafka character. On the other hand, one can have experiences that one recognises as Kafkaesque, while one would never call an experience of one's own Shakespearean or Dickensian.

'The Joker in the Pack' and 'Brothers and Others' are two of the finest twentieth-century essays on Shakespeare ; the first is on Iago as a practical joker, the second is on the homosexuality of Antonio in The Merchant of Venice and his connection with the play's other outsider, Shylock. There are also perceptive essays on Marianne Moore , Robert Frost , The Pickwick Papers , Don Juan and Italian opera.

The other notable feature of Auden's late career was his tendency to change, edit and cut his early poetry. He became obsessed with 'authenticity' and felt that much of his earlier verse was fake and dishonest. He particularly disliked 'Spain 1937' which he thought was hollow propaganda, and he removed it from later collections. He also had mixed feelings about 'September 1, 1939', especially the line 'We must one love another or die', which he changed to 'We must love one another and die'. There are few critics who believe that Auden improved his early verse with his amendments, and most contemporary editions of his verse use the original versions.

As well as poetry and criticism, Auden produced a wide amount of other material. He wrote three plays with Christopher Isherwood that are rarely staged, but which contain powerful poetry. The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), a farce about a boy who hides inside a dog costume, contains the poems 'The Summer holds: upon its glittering lake' and 'Now through night's caressing grip'. The Ascent of F6, published in 1936, is a play about a mountaineer whose psychological weaknesses prevent him from scaling F6. On the Frontier is about the romantic entanglements of two families, the Vrodnies of Ostnia and the Thorvalds of Westland. On moving to America, Auden wrote several librettos for operas with Chester Kallman. Their most successful collaboration was the libretto for The Rake's Progress (1951) by Igor Stravinsky.

Today Auden's critical reputation has never been higher. As a man, Auden impressed most of his contemporaries with his learned and witty conversation and his impulsive acts of generosity and kindness. He was cherished as an 'ami de maison' in spite of his innumerable eccentricities: his obsession with punctuality, his weird psycho-analytic theories, his massive appetite. He was also indifferent to hygiene: he never wore underpants, he liked to urinate in bathroom sinks, and he had a habit of publicly 'picking his nose and eating what he finds' (according to the novelist Paul Bowles). In many ways, Auden was an overgrown schoolboy ('It's such a pity Wystan never grows up' was a common refrain, according to 'Letter to Lord Byron'). However, this did not stop his friends treating him as an almost mythic presence, with a boundless intellect and an ability to dominate and transform any social event.

Since his death in 1973, there have been a profusion of academic studies on Auden. The two most useful biographies are by Humphrey Carpenter (published in 1981) and Richard Davenport-Hines (published in 1995). For a close reading of Auden's poetry, John Fuller is the most enlightening critic: his Reader's Guide to W.H. Auden was published in 1970 and W.H. Auden: A Commentary appeared in 1998. The other important Auden critic is Edward Mendelson: his two studies, Early Auden (1981) and Later Auden (1999), are full of excellent textual analysis. A broader perspective is provided by Samuel Hynes whose The Auden Generation appeared in 1976. Auden's contemporaries also wrote frequently and insightfully about the poet. Auden appears in the autobiographies of Stephen Spender ( World Within World), Christopher Isherwood (Christopher and His Kind ) and Louis MacNeice (The Strings Are False ). For a fuller understanding of Auden's verse, it is also well worth studying the poetry of Thomas Hardy , T.S. Eliot , Louis MacNeice and W.B. Yeats .

Frost, Adam

Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973

from Literature Online biography |

|

|

|

|

|

|

W.H. Auden(1907-1973)

W.H. Auden is widely regarded as the most important English poet of the past one hundred years. Writing in the Financial Times, Michael Glover has commented on 'the rise and rise of Auden's reputation until he is now considered one of the greatest -- if not the very greatest -- English poets of the 20th century'. Originally labelled a 'thirties poet', along with Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis, Auden is now seen as the representative twentieth-century artist and intellectual: his struggles with Freud, Marx, God and sexuality seem to epitomise and define his age. Originally infatuated with Pound and Eliot, he soon outgrew the esoteric tendencies of modernism, embracing the European poetic heritage in its entirety and experimenting with ballads, sonnets, epitaphs, odes, music hall ditties, folk songs and blues rhythms. Like Yeats, he believed passionately in reinvention and rediscovery, calling himself a 'traveller' on the 'journey of life', and constantly ditching poetic forms and registers as soon as he had mastered them. However, a recognisably 'Audenesque' voice is present in all of his best work: 'Lay your sleeping head, my love', 'As I walked out one evening', 'Musée des Beaux Arts', 'In Memory of W.B. Yeats' and 'The Fall of Rome'. This voice is intimate and bossy, earnest and funny, elegaic and impassive. Above all, its control of language is absolute. Auden's ability to choose phrases that are both appropriate and surprising remains the most enduring aspect of his legacy.

Auden was born in 1907, the third son of George Auden, a doctor, and Constance Bicknell Auden, formerly a nurse. Their marriage was not always a happy one, as Auden recalled in 1971: 'Ma should have married a robust Italian who was very sexy, and cheated on her. She would have hated it, but it would have kept her on her toes. Pa should have married someone weaker than he and utterly devoted to him.' George Auden moved the family to Birmingham in 1908, where he became a schools medical officer, responsible for improving public health in the largest industrial city in Britain. He was respected by his colleagues and remained in this position until his retirement in 1937. 'He was the gentlest and most unselfish man I have ever met,' Auden remembered. His mother was more stern and quarrelsome: a 'solemn, intense woman', according to Christopher Isherwood, whom Auden nevertheless adored.

Auden's parents influenced him in several ways. For a start, his father's medical background instilled in Auden a love of scientific enquiry that he never lost. As an adult, he would read books by archaeologists and psychologists as frequently as he would read books by poets and philosophers. His most famous poems are cold, clinical examinations of private and public illness. He found it so easy to embrace Freudian psychoanalysis in the 1920s and 1930s because he was already used to thinking in terms of sickness and cure. At the same time, his mother took control of his spiritual education. She brought him up as an Anglo-Catholic, insisting on family prayers before breakfast, and 'on Sundays there were services with music, candles, and incense' (as Auden remembered). Although he would lose his faith as an adolescent, this 'conviction that life is ruled by mysterious forces' would never leave him, and he would reconvert to Anglo-Catholicism in his mid-thirties. His mother also encouraged him to read and to appreciate music. When Auden was a boy, she introduced him to Tristan and Isolde , and mother and son would sing Wagnerian love duets to each other in the front room.

More generally, Auden would mythologise his mother and father and reintroduce them as symbols in his poetry. 'What is the use of pretending one can treat the members of one's own family as ordinary human beings?' he asked in 1963. A dominant mother would be the most dynamic feature of his first long poem, Paid on Both Sides. His play The Ascent of F6 was a study of Oedipal longings, and a grotesquely vengeful mother dominates the play The Dog Beneath the Skin. Similarly, father figures cast long shadows over The Orators and The Sea and the Mirror. Auden's habit of turning his parents into archetypes developed further after he discovered Freud and Jung in his early teens.

The other crucial event in Auden's early life was the First World War. It began when he was seven years old, and ended when he was eleven, dominating his childhood. In his early poetry, it is as if the war still continues: he is obsessed with soldiers and spies, vendettas and battles. More than any other poet of the 1930s, he lived in fear of the next war, convinced that the nations of Europe were destined to fight again. The first lines of his early poems reveal his preoccupation with military strategy: 'Control of the passes was, he saw, the key', 'We made all possible preparations', 'Pick a quarrel, go to war'. The First World War also left him with a lifelong fascination with heroism and sacrifice. Similarly, Auden became convinced that he would face a 'test' of his own, and glorified the idea of quests and missions.

In 1915 Auden was sent to boarding school at St Edmund's in Hindhead, and in 1920 he went on to Gresham's School in Norfolk. Looking back, Auden reflected: 'My political education began at the age of seven when I was sent to a boarding school. Every English boy of the middle class spends five years as a member of a primitive tribe ruled by benevolent or malignant demons, and then another five years as a citizen of a totalitarian state.' He remembered the teachers: 'Those who deep in the country at a safe distance from parents spend their lives teaching little boys, behave in a way which would get them locked up in ordinary society. When I read in a history book of King John gnawing the rush-mat in his rage, it did not surprise me in the least: that was just how masters behaved.'

However, at St Edmund's School, Auden made one of the most important friendships of his life: he met Christopher Isherwood. Although Isherwood was two years older than Auden, their shared sense of humour and passion for literature made them close acquaintances. At first Auden was determined to become a mining engineer 'and his playbox was full of thick scientific books on geology and metals and machines, borrowed from his father's library', as Isherwood remembered. However, during a walk with another friend, George Medley, in 1922, Auden was asked if he ever wrote poetry. From that moment, Auden single-mindedly devoted himself to verse and language, and began to write poems in the style of Wordsworth, Hardy and Walter de la Mare .

In 1925, Auden arrived at Christ Church College, Oxford, where he would stay for three years. He began as a student in natural science, then switched to Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE), then a few months later switched again to English. While at Oxford, he happened to meet Christopher Isherwood again and the two men began a long sexual relationship that lasted, on and off, until 1939. By this stage, Auden knew that he was a homosexual and began to write cryptic hints and allusions into his poetry. He also began to take Isherwood 's advice on which of his poems to keep and which to scrap. If Isherwood liked a single line from one poem, Auden would keep the line, often assembling entire poems in this fashion. This partly explains the fragmented, condensed, oblique nature of Auden's undergraduate verse.

Auden's time at Oxford has become mythologised by many of his contemporaries: Spender, MacNeice , Day-Lewis, Isherwood and others. He was ferociously well read and astonishingly precocious. By the age of twenty, he was co-editing a collection of Oxford Poetry. His tutor Nevill Coghill remembered: 'He had great intellectual prestige in the University at large.' Coghill also recalled: 'His sayings were widely misquoted and would appear, in their garbled form, in the essays of my other pupils. These being cross-examined, and their nonsense laid bare, still held the trump, which they would play when nothing else would save them: "Well, anyhow, that's what Wystan says".'

At Oxford, Auden also discovered Anglo-Saxon verse, a compulsory part of the syllabus that most students loathed but which Auden adored. His father had brought him up on Icelandic myths, and Auden often referred proudly to his 'Nordic' ancestors. Anglo-Saxon poetry would be a lifelong passion; Auden loved this world of liege lords, fallen warriors, hostile landscapes and gnomic, riddling wisdom. The second edition of his Poems (1933) contains a translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem, 'The Wanderer'. The early poem 'Control of the Passes' includes a quotation from 'Wulf and Eadwacer' and The Orators contains an extract from The Battle of Maldon.

The other major poetic influence on the young Auden was T.S. Eliot. He told Nevill Coghill: 'I've been reading Eliot. I now see the way I want to write.' For a while, his poetry was full of 'gasworks and dried tubers' (as he put it in 'Letter to Lord Byron') but later he came to disparage his Eliot phase as an artistic dead end. Certainly, he only found his voice when he shed Eliot 's disillusioned tone and replaced it with one of wariness and vigilance. Eliot believed in concentration, whittling down his poetry until he was left with 'a heap of broken images'. Auden would stress profusion and amplitude, trying out every conceivable poetic voice, compulsively dramatising each of his intellectual phases and moods.

After leaving Oxford, Auden spent nine months in Berlin with Isherwood and Spender. He preferred the austerity of the German capital to the clichéd aestheticism of Paris: for him Paris was 'the city of the Naughty Spree [. . .], bedroom mirrors and bidets, lingerie and adultery, the sniggers of schoolboys and grubby old men'. In Berlin he met John Layard, a disciple of Homer Lane, who introduced the poet to another batch of psychoanalytic theories. Essentially, Layard believed in acting on instinct, reversing guilt by turning its negative force into positive energy. Auden wrote in his journal: 'To cure a disease, encourage it, don't repress . . . Use love, not fear.' These ideas found their way into early poems like: 'Sir, no man's enemy, forgiving all' and The Orators . Auden fell out with Layard after the latter stole one of his boyfriends. Auden was furious with Layard: 'Tried to persuade him to kill himself', Auden wrote in his journal for 3rd April 1929. Layard duly went off and shot himself, missing his brain but putting a hole in his forehead. He then went round to Auden's house, delirious and bleeding, and asked the poet to finish him off. According to Layard, Auden said: 'I can't do it, because I might be hanged if I did. And I don't want to be.' However, on the whole, Layard was a positive influence on Auden who liberated him from feelings of guilt and encouraged him to embrace homosexual promiscuity. The two men maintained a loose acquaintanceship that lasted until the Second World War.

In July 1929, Auden returned to England. He had been briefly engaged to a nurse called Sheilah Richardson, but after his experiences in Berlin he broke this off immediately, writing in his journal: 'Never -- Never -- Never again.' He later told Naomi Mitchison that heterosexuality was 'like watching a game of cricket for the first time': 'I am not disgusted but sincerely puzzled at what the attraction is.' In April 1930 he secured a post as a teacher at Larchfield Academy, a boy's school in Scotland. Between 1932 and 1935, he was a teacher at the Downs School in the West Midlands.

During this period, Auden was establishing a reputation as the most promising young poet of his generation. In 1928, Stephen Spender had used a hand-press to publish twenty of Auden's 'Oxford' poems, several of which had attracted critical attention. In particular, 'The Watershed' seemed to represent a new kind of poetry, brilliantly tuned into the fears and hopes of the inter-war generation. The run-down industrial landscape of Auden's youth in the Midlands is turned into a general metaphor for the moral and social decline of Britain, the compressed and chilly diction emphasising the sense of isolation and fragmentation. Written when he was twenty, 'The Watershed' was Auden's first wholly successful poem, his first attempt to link private and public neuroses, his first successful synthesis of his psycho-analytic theories of free association and his modernist principles of clinical economy and linguistic collage.

But Auden's first public success came in 1930 when T.S. Eliot at Faber & Faber agreed to publish his Poems . Eliot had originally rejected a selection of Auden's work in 1927, but by 1930, Eliot had become convinced that Auden was an important new voice ('This fellow is about the best poet I have discovered in several years'). As well as half a dozen of the poems in Spender 's hand-printed volume, Auden's 1930 collection contained many of his most impressive early pieces, including 'Paid on Both Sides', 'It was Easter as I walked in the public gardens' and 'Consider this and in our time'.

'Paid on Both Sides' is a dramatic 'charade' about an obscure feud between bitter rivals in an unspecified country. At the beginning of the play, John Nower is planning to kill Red Shaw as an act of vengeance. Years before, Red Shaw killed Nower's father. After ambushing Shaw and murdering him, Nower marries Shaw's sister as a way of bringing peace to the country. However, Shaw's brother, Seth, is ordered by his mother to kill Nower on his wedding day. Nower is murdered and the feud continues.

At the same time, there are a host of secondary characters that demonstrate Auden's love of farce and music hall routines. A spy is tried by Father Christmas. A doctor appears to examine the spy and brings an impertinent servant with him. Rather than alleviating the atmosphere of doom and menace, these comic interludes only add to it, hinting at an underlying anarchy and lawlessness.

The rest of the poems in the collection share the same doom-laden, cold, forbidding landscape. Medical and military metaphors converge as Auden dissects a country that is either recovering from or entering into war. Where human communication occurs, it is in code, dense and difficult. The poet observes what is happening from a 'hawk's vision': he looks down like a general planning troop movements on a map, or a doctor looking down at T.S. Eliot 's 'patient etherized upon a table'. He is a 'tiny observer of enormous world', mimicking the 'hawk's vertical stooping from the sky'. His tendency is to generalise and to preach, but also to draw back from human contact.

Auden returns to the same concerns and pre-occupations in his next major work, The Orators (1931), a long, complex, multi-faceted poem which has the capacity to both confuse and enchant. The title is appropriate because the poem is essentially an excuse for Auden to try out different voices: he writes pastiches of rhetorical speeches, prayers, riddles, letters, dreams, journals, fairy tales and elegies. The poem begins with a Headmaster asking his pupils: 'What do you think about England, this country of ours where nobody is well?' The country is turned into a patient suffering from a psychological malaise. This idea is underlined in the section entitled 'Letter to A Wound,' in which a love letter sent by a patient to his mystery illness allows Auden to meditate on the curious appeal of pain and sickness.

The second section introduces the possibility of a hero to cure the ills of the nation. Auden told Eliot that: 'the central theme is a revolutionary hero.' In this way, The Orators is Auden's first real study of a potential political and spiritual saviour, a subject that he would return to in plays like The Ascent of F6. The hero in this case is a young aviator. His journal is full of information about fellow pilots and possible enemies, for example, 'Three kinds of enemy walk -- the grandiose stunt -- the melancholic stagger -- the paranoic sidle'. However, as the journal proceeds, it becomes apparent that the aviator is also psychologically ill, plagued by doubts and neuroses. He is especially haunted by the figure of an Uncle, his 'real ancestor' who inspired him to be a pilot.

The third section of the poem consists of a series of odes to Auden's friends. They are a combination of private jokes and public observations about Britain's sickness.

Five years after The Orators, Auden published his next major collection, Look, Stranger! (1936) (published in the United States the following year as On this Island). In this collection, although still fond of abstract and cryptic generalisations, he also began to associate writing with public duty, and consciously coined aphorisms that might sum up the moods and anxieties of Britain as a whole. In a sense, his ideological allegiance had shifted from Freud to Marx, and he began to treat 'neuroses' and 'repression' as political problems. At the same time, his more private and intimate poems dispensed with the paranoid encryption that was such a feature of his earlier work. Cautiously and gradually, Auden began to admit his need for love and his faith in friendship.

The most stirring public pronouncement in the volume is probably the title poem, which begins:

Look, stranger, at this island now

The leaping light for your delight discovers,

Stand stable here

And silent be,

That through the channels of the ear

May wander like a river

The swaying sound of the sea.

This represents a turning point in Auden's career: for the first time, he was identifying both with the British public and with the 'stranger'; he was looking at his country as an insider and an outsider simultaneously.

Auden also began to write more intimate poems like 'Out on the lawn I lie in bed' which is a hymn to friendship, a celebration of a truly happy and unrepeatable period of companionship:

Equal with colleagues in a ring

I sit on each calm evening,

Enchanted as the flowers

The opening light draws out of hiding

From leaves with all its dove-like pleading

Its logic and its powers.

The collection also contains more mature formulations of Auden's earlier preoccupations, such as a sonnet about heroism, loosely based on Lawrence of Arabia and sometimes known as 'Who's Who'.

In 1935, Auden gave up teaching and spent four years leading a somewhat nomadic existence. Between 1927 and 1935 he seemed to be on an intellectual quest, reading Freud , Marx and T.S. Eliot. After 1935 this became a geographical quest, and he visited Spain, Iceland and China, and finally moved permanently to the United States in 1939.

The last few months of 1935 were spent working on a documentary for the Post Office. The lines he provided for Night Mail would become some of the most famous in his oeuvre:

This is the night mail crossing the border,

Bringing the cheque and the postal order,

Letters for the rich, letters for the poor,

The shop at the corner and the girl next door.

In June 1935 Auden married the German Erika Mann, in order to provide her with a British passport and an escape from the Nazis ('What are buggers for?' he commented). In 1936 he spent the summer in Iceland with Louis MacNeice, producing the collaborative collection, Letters from Iceland ; in 1937 he drove ambulances for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, writing the poem 'Spain 1937' shortly afterwards; in 1938, he went to China with Isherwood, after Faber commissioned a travel book on the war in the Far East, and in summer 1938 he visited New York for the first time.

Letters from Iceland (1936), written with Louis MacNeice, is one of the best-loved collections of British poetry of the twentieth century. Written in a holiday spirit, it contains a mixture of great poetry and forgettable whimsy and survives as a testimony to the close friendship of these two formidable writers. Both poets produced some of their finest work ( MacNeice 's 'Postscript to Iceland' and Auden's 'Journey to Iceland' and 'Letter to Lord Byron'). For Auden in particular, exploring his Nordic roots was an almost mythic experience.

'Letter to Lord Byron,' probably Auden's greatest long poem, sits at the centre of the volume showing just how far Auden had progressed from the gnomic, stunted verse of 'The Watershed'. The poem consists of a series of witty and insightful observations about the state of Britain and the condition of W.H. Auden in the summer of 1936. He praises 'novel writing' as a 'higher art than poetry; discusses his love of industrial landscapes; talks about how the world has changed since Byron's day; defends light verse and argues that poetry must be varied; dismisses nature poetry and asserts:

To me Art's subject is the human clay

And landscape but a background to a torso.

He identifies himself with society poets like Dryden , Pope and Byron . After describing his personal appearance to Byron , he goes on to explain why he feels the need for this poetic confession:

So I sit down this fine September morning

To tell my story. I've another reason.

I've lately had a confidential warning

That Isherwood is publishing next season

A book about us all.[. . .]

Isherwood 's 'revelations' were not dramatic enough to stop the two writers going to China in 1938. The book they produced contains a sonnet sequence by Auden, 'In Time of War', that is both a technical triumph and an insightful meditation on the effects of war.

Another Time, published in 1940 after Auden's move to the States, is generally regarded both as his finest single volume and one of the greatest collections of poetry in English literary history. Like Hardy 's Satires of Circumstance (1914), Hopkins 's Poems (1918) or Eliot 's The Waste Land (1922), it was a collection that seemed to change forever the way in which poetry was read and understood. It contains nearly all of Auden's greatest verse: 'Lay your sleeping head', 'As I walked out one evening', 'Musée des Beaux Arts', 'Spain 1937', 'In Memory of W.B. Yeats', 'September 1, 1939', his three ballads, 'Miss Gee', 'Victor' and 'James Honeyman', the series of poems on other writers, 'A.E. Housman', 'Matthew Arnold', 'The Novelist' and 'Edward Lear' and the series of lyrics and songs, 'O tell me the truth about love', 'Funeral Blues' and 'Refugee Blues'.

'Lay your sleeping head' is a celebration of an uneven, flawed love affair. Rather than idealise the beloved, he is 'mortal, guilty', similarly the poet is 'faithless' and their love is 'ephemeral'. Nevertheless, they have a moment together and its perfection is dependent upon an honest acknowledgement of their relationship's frailty. 'Spain, 1937' is a 'hawk's eye' view of the Spanish Civil War, placing the conflict in the context of History. Using repetition and rhetoric, Auden looks at Spain 'yesterday', 'today' and 'tomorrow'. Auden also shows how the Spanish Civil War was a different experience for each participant, young poets and writers imposing their own private conflicts onto the country. British intellectuals wrote constantly about Spain in the 1930s, and Auden's poem can usefully be compared to Orwell 's Homage to Catalonia and Section VI of Louis MacNeice 's Autumn Journal. (Indeed MacNeice later commented: 'We needed Spain more than Spain needed us.').'Musée des Beaux Arts' is a poem about suffering and indifference. Auden is looking at Old Masters in a gallery and notices a discrepancy between the suffering and ecstasy of saints and religious icons, and the inevitable impassivity of bystanders (and those who look at the paintings).

'In Memory of W.B. Yeats' is both an appreciation of the Irish poet and a summary of Auden's thoughts on poetry in January 1939. The first section focuses on Yeats 's actual death; the second is a meditation on his verse; and the third is a series of couplets on the subject of art and time:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

'September 1, 1939' is generally regarded as Auden's masterpiece, his complex reaction to the war that he always knew was coming. At the time Auden was in America, and the mixture of detachment from the European scene and complete absorption in the apocalyptic situation is what gives the poem its uniquely wise and humane tone. After noting a universal mood of anger and fear, Auden proceeds to look at the causes of the war, blending his views on history, psychology and religion, mentioning Luther, Hitler and Thucydides. At the end of the poem, Auden tries to come to terms with his feelings of powerlessness and anger. His poem becomes a defiant response to the 'international wrong'. He will ignore 'the lie of Authority' and the falsifications of History and place his trust in humanity: 'We must love one another or die.' In the face of World War, Auden advises a limited, cautious amount of hope. He is 'beleaguered by the same / Negation and despair' but he will 'show an affirming flame'.

By 1940, Auden and Isherwood had moved to the United States permanently. This caused a huge amount of resentment in Britain; they were depicted as 'deserters' who had abandoned their country in its hour of need. Evelyn Waugh portrayed them as 'Parsnip and Pimpernel', two camp and pretentious cowards, in his 1942 novel Put Out More Flags. Reviewing Spender 's memoirs in 1951, Waugh also accused Auden of fleeing to the States 'at the first squeak of an air raid warning'. However, Auden was no coward: he had been involved in wars in China and Spain and in 1942 he was happy to appear before the US military draft board. He was turned down by the army on the grounds of his homosexuality.

Two other incidents transformed Auden's life in America. He met Chester Kallman and he reconverted to Anglo-Catholicism. Kallman was 18 when he met Auden at a poetry reading in 1939. Kallman had always intended to flirt with the poet, telling his friend before the reading: 'Did you know that Auden and Isherwood are reading on West Fifty-Second Street next week? Let's sit in the front row and wink at them!' However, this casual affair would turn into the most enduring and meaningful relationship of Auden's life. For Auden, he and Kallman were like husband and wife: he wrote to his brother John in May 1939, 'it's really happened at last after all these years. Mr Right has come into my life [. . .]. This time, my dear, I really believe it's marriage.' Auden and Kallman had much in common, including a love of psychoanalysis and self-dramatisation that frequently led to heated exchanges, such as this argument on a train in 1940. 'Passengers stared in disbelief' as Auden and Kallman screamed:

WYSTAN: I am not your father, I'm your mother .

CHESTER: You're not my mother! I'm your mother!

WYSTAN: No, you've got it all wrong. I'm your mother!

CHESTER: You're not. You're my father .

WYSTAN: But you've got a father. I'm your bloody mother and that's that, darling! You've been looking for a mother since the age of four!

CHESTER: And you've been obsessed with your mother from the womb! You've been trying to get back ever since, so I am your mother! And you're my father!

WYSTAN: No, you want to replace your father for marrying women who rejected you, for which you can't forgive him. But you want a mother who will accept you unconditionally as I do...

CHESTER: I'm your goddamn mother for the same reason.

The most painful event of Auden's life took place in 1940 when he realised that Kallman had been unfaithful to him and always would be unfaithful. Their tortuous but lifelong relationship inspired some of Auden's most moving and troubled later poetry.

In America, Auden also rediscovered God. In November 1939, he went to a German-language cinema that was showing a Nazi propaganda film before the main feature. Auden was appalled when German audience members reacted to the appearance of Poles and Slavs on the screen by screaming: 'Kill them!' This sudden encounter with 'the evil incarnated in Hitler' inspired Auden to return to the Church. Christian imagery had been a feature of much of his earlier verse, like 'No man's enemy, forgiving all' and the sonnet 'Certainly praise' from In Time of War. However, by 1939, he was ready for the discipline and comfort of active faith. His Christianity became more pronounced after the death of his mother in 1941, and he wrote the Christmas Oratorio, For the Time Being (1944), in her honour. The sequence of religious poems, Horae Canonicae, would be written between 1949 and 1954. At the same time, Auden's faith was never strictly conventional. He took to referring to the deity as 'Miss God' (for example, he said of homosexuality: 'Of course it's a sin. We just have to hope that Miss God will forgive us.'). He also managed to turn much of the Bible into a psychoanalytic case study.

The poetry that Auden produced after his move to the United States provoked distinctly mixed reviews. Philip Larkin 's rhetorical question ('What's become of Wystan?') was a representative response. Auden's post-1939 work seemed to head in two directions: it was either dense philological game-playing with a religious tinge, or simplistic light verse written with a prosy casualness. It lacked the authority and energy of the '30s poetry. It seemed to turn in on itself: its subject matter was art not life. Since Auden's death in 1973, this critical consensus has been modified slightly. Although Auden's late verse is still not regarded as highly as his '30s output, many of his later lyrics, like 'The More Loving One', 'Their Lonely Betters' and 'The Fall of Rome' have been praised, as has the long poem 'The Sea and the Mirror'. Edward Mendelson's book, The Later Auden (1999), has been instrumental in resurrecting Auden's 'American' reputation.

Certainly Auden was prolific in the United States. New Year Letter, written in 1940 and published in 1941, was a long poem in octosyllabic rhyming couplets about art, war and faith, followed by eighty-one pages of prose notes. He wrote the long epithalamium 'In Sickness and in Health' in 1940; he published the elegy 'At the Grave of Henry James' in Horizon in 1941. He supplied the libretto for Benjamin Britten 's Paul Bunyan, first performed in 1941. Another long poem, For the Time Being, followed in 1944, and another, The Age of Anxiety, appeared in 1947. He began writing the sequence Horae Canonicae in 1949.

However, the greatest work of this period is probably The Sea and the Mirror (1944), a lengthy poetic response to Shakespeare 's The Tempest. Frank Kermode has described it as 'the peak of Auden's achievement'. The Tempest is an appropriate subject for Auden because after 1939 he has much in common with Prospero -- an exile whose artistic authority cannot mask his profound melancholy.

The Sea and the Mirror is a series of monologues in which all the play's characters reveal their true natures and also make more general points about the role of creativity in a fallen world. In the first section, Prospero is the poet meditating on his art; the second section is a series of poems spoken by the 'supporting cast', all of whom are undermined by refrains from the malevolent Antonio; the third section, a prose address entitled 'Caliban to the Audience', is usually described as the most successful part of the poem. This is a celebration of the vulgar and bestial in art. Caliban's humanity is compared to the audience's -- together these mortal agencies are contrasted with the 'high strangeness' and separateness of immortal art. Caliban argues that the audience wants Art and Life to be distinct. Moreover he suggests that both Art and Life are essential, to dwell permanently in either would be terrifying, to be 'released' from life into art is as vital as being 'released' back into life at the end of a play or poem. The actors too need 'that Wholly Other Life' that lies across 'an essential emphatic gulf' symbolised by 'mirror and proscenium arch'.

Other important poems of Auden's late period include 'In Praise of Limestone' (written in 1948), 'The Fall of Rome' and 'The Shield of Achilles' (both published in 1955 in the collection The Shield of Achilles ) and 'The more loving one' (published in Homage to Clio in 1960). These poems all possess the exile's melancholy and detachment. 'In Praise of Limestone' is a reflection on the English countryside that he had left behind in 1939. 'The Fall of Rome' is in many ways a recapitulation of many of Auden's '30s obsessions, since it evokes a general atmosphere of threat and menace, and hints at the imminent collapse of civilisation. The simplicity of diction in this poem is typical of the later Auden, as is his tone of impotent mourning. A comment he made in the 1950s reveals a similar mood of resignation: 'One ceases to be a child when one realizes that telling one's truth does not make it any better. Not even telling it to oneself.' 'The Shield of Achilles' is one of Auden's most widely-praised later poems. On the simplest level, it is about a shield made by Hephaestos for Thetis, but on another, it is about the duty of art to reflect sorrow and suffering, and the disappointment of readers who expect poetry to be celebratory. Like 'The Fall of Rome', 'The Shield of Achilles' is about powerlessness in the face of violence and death. But it is also about the responsibility of the artist to stand outside his age, and 'undo the folded lie'. Hephaestos has to depict the truth as he sees it, whether he wants to or not.

Another explanation for the apparent waning of Auden's reputation in America is the claim that, after 1939, he became a reader, not a writer, a critic, not a poet. Indeed, along with T.S. Eliot, he became one of the most highly respected literary critics of the twentieth century. The Dyer's Hand, published in 1963, contains some of the most influential essays of the late twentieth century: 'To get a true idea of them, one must imagine Coleridge as a man of the 1950s and 1960s', the Sunday Times commented. Forewords and Afterwords, published in 1973, is an excellent companion piece, containing Auden's collected book reviews.

The Dyer's Hand is written largely in note form, 'because as a reader, I prefer a critic's notebooks to his treatises', Auden explained. It contains some of his most important pronouncements on poetry and history. For instance, in the essay 'Reading', he declares:

As readers, most of us, to some degree, are like those urchins who pencil moustaches on the faces of girls in advertisements.

In general, when reading a scholarly critic, one profits more from his quotations than from his comments.

One cannot review a bad book without showing off.

A writer, or at least, a poet, is always being asked by people who should know better: 'Whom do you write for?' The question is, of course, a silly one, but I can give it a silly answer. Occasionally I come across a book which I feel has been written especially for me and for me only. Like a jealous lover, I don't want anybody else to hear of it. To have a million such readers, unaware of each other's existence, to be read with passion and never talked about, is the daydream, surely, of every author. In the essay, 'Writing', he comments:

Every 'original' genius, be he an artist or a scientist, has something a bit shady about him, like a gambler or a medium.

What makes it difficult for a poet not to tell lies is that, in poetry, all facts and all beliefs cease to be true or false and become interesting possibilities.

Every work of a writer should be a first step, but this will be a false step unless, whether or not he realize it at the time, it is also a further step.

The poet who writes 'free' verse is like Robinson Crusoe on his desert island: he must do all his cooking, laundry and darning for himself. In a few exceptional cases, this manly independence produces something original and impressive, but more often the result is squalor.

Poetry is not magic. In so far as poetry, or any other of the arts, can be said to have an ulterior purpose, it is, by telling the truth, to disenchant and disintoxicate.

'Making, Knowing and Judging' and 'The Virgin and the Dynamo' are good accounts of Auden's poetic evolution and his theoretical beliefs. In 'The Poet and the City', he looks at how the Industrial Revolution has changed art and society, placing particular emphasis on the transformation of technology, science and religion. He also begins to characterise poetry as a game or sport. Other essays, like 'Hic et Ille' and 'Balaam and His Ass' contain his eccentric views on selfhood, love and the division between the sacred and the profane. 'The Guilty Vicarage' is a seminal essay on detective fiction, in which he argues that the genre indulges the fantasy 'of being restored to the Garden of Eden'. In 'The I Without A Self', he attempts to analyse Kafka 's parables:

Sometimes in real life one meets a characters and thinks, "This man comes straight out of Shakespeare or Dickens ", but nobody ever met a Kafka character. On the other hand, one can have experiences that one recognises as Kafkaesque, while one would never call an experience of one's own Shakespearean or Dickensian.