|

5 pm, February 25, 2016 Room 7.45, Run Run Shaw Tower, Centennial Campus English Studies in Asia, Does It Make Sense? Chankil Park(Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea)

Introduction

Hello!

My name is Chankil Park. I am a professor of English poetry teaching at Ewha

Womans University at Seoul. My original mission was to have a meeting with the

faculty members of the School of English here at Hong Kong University to

establish a special exchange agreement at the departmental level. When we

contacted professor Dirk Noel, he not only accepted our request of meeting, but

also kindly invited one of the delegation to the talk in your seminar series. I

agree totally with him that a discussion through an academic discourse would be

a natural way of knowing each other, particularly for the academics like

us. Thank you again for your thoughtful

invitation, and it is absolutely a pleasure meeting you and an honor of mine to

have a chance to talk to you here at Hong Kong University. Thank you also other

professors, students who have joined us today. I will do my best to make my

point as shortly, as less boringly as possible.

I

am a scholar of British Romanticism by training, but the title of my talk today

is, "English Studies in Asia: Does It Make Sense" As a scholar of

English located in Asia, I have never been free from such self-consciousness

ever since I started my work as a full time faculty of English Literature 22

years ago because I have been living and working in so-called “periphery” of

the scholarship of English where an academic achievements in such a discipline

are very much likely to be underestimated or ignored both within and without

region. The following thoughts are a result of my experience as a scholar of

British Romanticism located at the periphery.

1.

The "Crisis" Narrative of English Studies in Anglophone Academia

The

"crisis" of English Studies in Anglophone Academia has long been a

commonplace. Ever since Bill Readings published The University in Ruins(1996)

where he cogently analyzed how the university had been deteriorated from her

ideal form, so many scholars have played the similar tunes, the tunes of

anxiety, anger, and lament over the downfall of the university and the collapse

of liberal education. Harry R. Lewis’s Excellence

Without A Soul: Does Liberal Education Have a Future?(2006), Ellen

Schrecker’s The Lost Soul of Higher

Education: Corporatization, The Assault on Academic Freedom, and the End of the

American University(2010), Martha Nussbaum's Not for Profit(2010),

Benjamin Ginsberg's The Fall of the Faculty(2011), Frank Donahue's The

Last Professors(2011), to name a few, have all tolled the knell of the

University, the University where relatively small number of students are taught

by tenured professors within a well-developed liberal education program

consisting of the canonical works of great authors such as Homer, Plato, or William

Shakespeare. More recently, Paul Jay, in his The Humanities

"Crisis" and the Future of Literary Studies(2014) seems to take a

more balanced stance on this matter. His comments are of particular pertinence

to us because his book recapitulates all the major "crisis"

narratives published in the last couple of decades in a wider historical

context with a particular concern over the declining literary studies in the

North American Universities. His summary of the "crisis" sounds

familiar but seems universally true. I will start quoting a passage from his

introduction to remind ourselves what predicament we all of us are facing in

our universities whether we are in the center or periphery.

The

humanities today seem the victim of a perfect storm. Budget cuts stemming from a persistent

recession, accompanied by the defunding of public institutions of higher education

through shrinking tax revenue, have threatened humanities programs everywhere.

The corporatization of higher education has increasingly turned university

presidents into CEOs, and academic administrators into upper management. The decisions they make regarding academic

programs are increasingly driven by boards of trustees dominated by

businessmen, bankers, and financial consultants whose bottom-line methods of

operation are taking precedence over the traditional role faculty have played

in determining academic and curricular programs. In this context, higher education is

increasingly seen in sheerly instrumental terms, with courses and programs

judged in terms of their pragmatic and vocational value. Education that ends in

credentializing seems to be trumping education as an end in itself. For many,

the teaching of practical skills is becoming more important than making sure

students have a basic knowledge of history, philosophy, literature, and the

arts. With the value of education being measured more and more by the economic

payoff that comes after graduation, it is becoming difficult for many to

understand the value of a humanities education.

2.

A Story of Korean Universities: Crisis or Not?

Let

me tell you a little bit about Korean situations in relation with the things

Paul Jay mentioned above:

Budget Cut.

The 2014 educational statistics in Korea shows that the Humanities occupies

about 2.2% (71m us dollars) which is of course a decrease from previous years.

But in Korea, the absolute amount of educational budget is less a problem than

how to use them. The problem is that the government wants to use the R & D

money not as a way of encouragement, but of restructuring and reduction of an

academic field. Free competition for the money leaves only a few in the field.

Even in those lucky few, scholars exhaust their energy not with teaching or

research but with the paper works related to the research grant. You must know

what I mean.

Corporatization.

Just like companies are estimated with profit, universities are estimated with

ranking. QS, The Times, Shanghai Zaotung, Leiden Ranking internationally,

Ministry of Education, Joongang Daily, Chosun Daily domestically, all these

companies or institutions are publishing the hierarchy of the universities. No

universities are free from their evaluations, and they commit themselves to an

unending race to get a better place in the table they draw at their will. Their

evaluations are based on many parameters, of course. But the simplest and

clearest indicator of the quality of researches carried out in a university is

the total amount of R & D money. (In this respect, the humanities is almost

a meaningless factor.) Just like a company is estimated in terms of annual

sales, a university is estimated in terms of the total amount of research

grant. Money means everything also in the university.

Pragmatic and vocational value.

We all know that the rate of employment is getting more and more important in

estimating our “utility” individually or collectively. In comparison with other

humanities subjects such as history or philosophy, English department may be

relatively ok as far as the employment rate is concerned. But I cannot forget a

special lecture given to the whole faculty of my university a few years ago by

the director of a research institute affiliated with Samsung Group who happened

to be a professor of management at our neighbor university. He was talking

about the role of university in a globalizing economy, and concluded his

lecture with downright conviction saying that "You professors's sole

mission here in the university is to grow your students into the talent that is

worth "an entry annual salary of 200,000 US dollars." (I was shocked

with two things: the target salary was way too high in comparison with mine,

and of course his impudent provocation and simple unabashedness. How dare he

say such a thing to his fellow professors?)What a shame!

Education that ends in credentializing.

Getting a job is becoming more and more important to students. Our

undergraduate is a 4 year program with 2 semesters a year. Companies are

beginning to recruit a new employee from October or November which are well

within the second semester. Students in their final semester have no qualm in

applying for the places that do not wait until they complete the final semester

in December. Perhaps 10 years ago, I simply kicked them out even before they

try to "negotiate" with me. Now I am ashamed that I find myself

willing to "negotiate" with them first. If not making them worth

200,000 US dollars, how could I block them to make a living with a regular job

which was one and only objective of university degree in the first place?

Besides, it would make our department employment rate even higher!

Perhaps

I can go on like this cynically making fun of myself and my fellow professors

who are suffering from serious identity crises.

3.

The Identity Crisis of English Scholars in Asia: English Teacher or Scholar?

Yes.

we are suffering from identity crisis, perhaps with somewhat different reasons

from those of Western English scholars. Located in Asia, to whom should we make

our academic contributions? As a researcher, I could perhaps write for the

world if I write in English. But most of my research papers have been written

in Korean for multiple reasons. First, English is not my native language and it

is not very convenient vehicle of writing taking long time to publish. We are

required to publish 1-2 articles every year and we are evaluated every year by

the university. Besides, it is very difficult to believe that Wordsworth

scholars of Anglophone world are waiting for my academic contribution more

eagerly than those in Korea. Of course I cannot be sure about my Korean

colleagues. Then for whom should my academic activities be done? Obviously, it

is more reasonable that the place to which my academic contribution should be

made is Korea, the place I live. Then what does it mean to be a professor of

English Literature in Korea?

(Well,

the fact that English is not my native language is of course a handicap but an

advantage. As a scholar of English Literature, my "accessibility" to

the texts in English cannot but be evidently lower than my counterparts in the

Anglophone academia. But in my own community, my English proficiency is much

more, much readily appreciated than in the West, which is the reason why a

teacher of English Language is the most readily accepted professional identity

that I am accredited with in my own country. But it was the case only before

Korea opened its gate to the global market of English education. We started to

"import" English teachers from the Anglophone world, and it was them,

"English Native Speaker Teachers" who began to take over the responsibility

of English Teaching from us the English Literature professors. Outside the university, the layman, who used

to "respect" us as "experts in English," came to believe

"Native Speaker Lecturers of English Conversation" more than English

scholars of Wordsworth or Shakespeare. As a matter of fact, we Korean

professors of English do not regret particularly that we no longer function as

English teachers. We do not appreciate the job of teaching "College

English" to the freshmen or making English tests for all kinds of entrance

exams which used to be carried out usually by junior staff or part-time

lectures.)

The

professional identity we ourselves assume is a scholar of English literature or

linguistics regardless of the working location. We perform our academic work

for an imaginary general public in and out of the country who are supposed to

read our papers . We have not had any particular awareness of our nationality

or national identity when we teach English Literature or English Linguistics to

our students whether they are Korean or not.

We have not assumed any particular nationalities as our main readership

when we write our research papers. If we are required to justify our

professional contributions to our community we live in, will it be ok to go on

like this? How could we cope with their barbarous treatments of our profession

if we cannot prove our "utility" in those terms that would be

understandable even to them.

4.

The English Scholar as a Translator of Culture

(I

am not representing all Korean professors of English Department, not even those

of my own department where 17 full time professors (apart from myself prof.

Choi over there) are working. There are about 2,600 full time teaching staff of

English Literature or Linguistics in 202 4 year universities in Korea. They

must be very diverse and disparate in their sense of professional identity and

social contributions. So, the following thoughts are entirely mine based on my

own experience of 21 years as a teacher and a scholar in Korea.)

I

have always thought that the role of Korean scholar of English Literature was

that of a translator, the translator not only of language, but more

significantly of culture. Korea was opened by force in the late 19th century by

foreign countries, particularly by the imperialistic Japan which had

preemptively taken the modernity of the West through Meiji Innovation. That

modernity was enforced upon Korea by Japan for 36 years through their colonial

domination of Korea between 1910 and 1945. After getting the independence from

Japan in 1945, US replaced Japan as a model of modernization. Whether or not we

like it, there is no way of understanding the modernity of Korea without Japan

and United States. The modernity of the West which was "translated"

by Japan, the modernity of the West which was "adapted" by the United

States were indeed the driving force behind the modernization of Korea, and it

was Korean scholars of English Literature who had first understood those

particular models of modernity in Korea. If it was UK(as was translated by

Japan) and US that had been playing the most dominant roles in establishing the

World Order since the 19th century, it was Korean scholars of English

Literature who "translated" the best part of their modern civilization

into our own cultural resources. It was obviously the contribution they had

made far more important than simple teaching of English language.

5.

The English Scholar, a Local Agent responsible for imparting the ideology of

postcolonial colonialism?

I

know that my idea sounds like Arnold's: a civilized man pursuing perfection

making "the best that has been thought and known in the world current

everywhere." I am also aware of Edward Said's critique on Arnold. Our

naive acceptance of what he described as "sweetness and light" simply

as "the best" achieved by mankind could make us blind to the sinister

nature of the cultural strategy of imperialism, and some may well think that

we, perhaps without our knowledge, are working for the colonialists, working as

the "local agents" of their cultural apparatus to impart the

postcolonial colonialism. The Asian scholars of English might never be entirely

free from such suspicion. It is undeniably evident that the scholars located in

the "periphery" tend to be oriented towards the "center."

My own department, for example, has 19 full time faculties and 17 of them have

American or British Ph D, I do not see anything qualitatively different in their

teaching and research from those of their counterparts in the

"center." We both of us have been colonies once and the

decolonization must be an important social issue to both of us. I understand

that the decolonization process in Hong Kong could involve an even trickier

problem: how to establish a new social order which would be acceptable to the

Mainland China without sacrificing the democracy you have been enjoying under

the colonial regime. As far as the

decolonization is concerned, Korea is not an easy case either. Japan, the old

colonial power, is still not genuinely regretful of their colonial domination

in the past. Both Korea and Japan have been staunch allies to Unites States

economically and militarily ever since 1945, but US has never clearly taken

Korea's side in the long history of our ideological conflicts with Japan. If I

am allowed to simplify, I would summarize like this: US has always supported

Japan more than Korea especially in relation with our decolonization process

because US has always been more interested in maintaining status quo in

this region than making Korea a really independent country free from its

colonial inheritance. The point is that the issue of decolonization is very

much alive both in Hong Kong and Korea in the contemporary politics. My

question then is how could we justify our profession of an English scholar, the

"problematic" scholarship under the suspicion of collaboration with

the old(and new) colonial power? How could we make our translation of their

best "culture," a real enrichment of our intellectual resources, not

a propagation of a new colonialism which often disguises itself as

transnational capitalism or neoliberalism. Knowing that the "great

tradition" of English literature was in fact "planned and

produced" as a part of the cultural strategy of imperial Britain, how

could we make the essence of their real creative achievement as our own without

succumbing to its possibly colonialistic purport.

6.

A Personal Recollection: Military Dictatorship in Korea(1961-87) and University

Students's Roles in Democratization Movement

At

this point, I cannot help being self-confessional. I was very much

self-conscious of the political implication of my academic pursuit from its

very beginning. I entered the university back in 1980 right after President

Park, Korea's first military dictator who was father of the current president

Park, was shot dead by one of his subordinates. It was when everybody was

dreaming of a rosy future of democracy in Korea, and the university was the

very center of such a political idealism. In Korea, many intellectuals including

writers, journalists, and university professors participated actively in the

democratization movement against General Park's government between 1961-79.

University Students, though young, were always the main component in the street

demonstration. I started my university life in such an atmosphere. However, we had another military dictator,

General Chun, who took the power after he had suppressed people's revolt at

Kwangju killing hundreds of rebellious citizens.

It was May 1980, only 2 months

after I entered the university. It was an age of violence to which students

responded with violence. Street demonstrations were a part of our daily lives

during which many friends of mine got arrested, imprisoned, even killed. I was

not an active member of political movements, but did share, as it were,

"the spirit of the age" like anybody else.

7.

William Wordsworth, a Revolutionary Poet

That

was why I was attracted to the story of William Wordsworth who was known as a

poet of revolution who had personally witnessed the very early stage of the

French Revolution. I tried to read Wordsworth's poetry in the context of his

political imagination, which could be, I thought, my own political engagement

through my academic pursuit. It was a naive thought of course because reading

revolutionary poems is one thing, and participating in the real politics

entirely another. And Wordsworth's

radicalism itself turned out to be much more short-lived than I had hoped it

would be. It took only less than a decade for a revolutionary poet who

declared,

Bliss

was it in that dawn to be alive,

But

to be young was very Heaven! ...

When

Reason seemed the most to assert her rights

When most intent on making of herself

A prime enchanter to assist the work,

Which then was going forwards in her name!

(ll.

108-109, 113-116, Book X, The Prelude, 1805)

to

become the one who claimed,

O for the coming of that glorious time When, prizing knowledge as her noblest wealth and best protection, this imperial Realm, While she exacts allegiance, shall admit And obligation, on her part, to teach Them who are born to serve her and obey; (ll. 293-298, Book IX, The Excursion, 1814)

Percy

Bysshe Shelley who had actually been one of the most devoted disciples of

Wordsworth, exclaimed with lament that “What a beastly and pitiful wretch that

Wordsworth! That such a man should be such a poet!” It was a great

disillusionment to me to recognize later that his celebration of "that

glorious time" turned out to be a proleptic expression of British imperialism

and his attachment to British land as was warmly expressed in

"Michael" was to be used as the spiritual foundation of the British

imperialism as was recently indicated by some romantic scholars. Isn't it a

typical example of a dramatic irony that my choice of subject, apparently

motivated by the political subconsciousness of a would-be anti-colonialist

literary scholar proved to be the very origin of the British colonialism? But I

do not have any regret of having become a scholar of Wordsworth because what I

had liked (and continue to like) in Wordsworth was his early poems inspired by

his political idealism he learned for Michael Beaupuy, a revolutionary army

officer and his passionate love of democracy. What enabled him to conceive such

idealism all against the main current of British politics was the fact that he

was absolutely alienated from the center of British cultural circles.

Wordsworth was spiritually an exile all along his radical years of the 1790s.

When he heard the defeat of British army at the Battle of Hondschoote on

September 8 1793, for example, Wordsworth felt himself typically as the one

"like an uninvited guest" in his home country.

When Englishmen by thousands were o'erthrown, Left without glory on the field, or driven, Brave hearts! to shameful flight. It was a grief, Grief call it not, 'twas anything but that,- A conflict of sensations without name, ...And, 'mid the simple worshippers, perchance, I only, like an uninvited guest Whom no one owned, sate silent, shall I add, Fed on the day vengeance yet to come? (ll.262-266, 272-275, Book X, The Prelude 1805)

His

expectation of "the day vengeance" was surely unpatriotic, but his

sense of alienation in which he was able to remain intact from the 'Church and

King" patriotism was the very condition for his political insight to see

through the parochial narrow-mindedness of many British intellectuals who had

quickly turned their backs to the political idealism of the French Revolution

to which they also had welcomed at first. Wordsworth's political idealism was

made possible by a kind of cosmopolitan point of view he had adapted from a

French army officer who was absolutely “external” to British tradition. We all

know that Wordsworth lost his poetic creativity exactly when he began to settle

into British soil, recovering his sense of national identity as a British

subject as was indicated by his accepting the appointment of the distributor of

stamps in 1813.

8.

Lord Byron and the Value of the "Otherness"

Such

"externality" or “otherness” to the parochial nature of British

culture Wordsworth had once shown was inherited by Lord Byron whose political

idealism was in fact anything but British. He was not only physically expelled

from British soil, but spiritually exiled far into Europe. Childe Harold, his poetic avatar, is really a

character of European cast into which he was built by Byron's own Grand Tour,

the educational program for British aristocracy to go beyond the parochialism

of British culture. Byron's Childe Harold Pilgrimage is to me a kind of

poetic antithesis Byron had to construct outside Britain as an antidote to

Wordsworthian egotistic sublimity Wordsworth had been establishing on the

British soil. Byron's "unpatriotic" but historically correct

reflection is made when Harold stands upon the place of Britain's historical

victory over Napoleon at which many British travelers would have nothing but

rapturous feelings of national pride. Byron's response was far different.

Fit

retribution - Gaul may champ the bit

And

foam in fetters - but is Earth more free?

Did nations combat to make One submit:

Or

league to teach all kings true Sovereignty?

What! shall reviving Thraldom again be

The patched-up Idol of enlightened days?

Shall we, who struck the Lion down, shall we

Pay the wolf homage? proffering lowly gaze

And servile knees to thrones? No; prove before ye praise!

(ll

163-171, Stanza 19, Canto III, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage)

Byron's

clear-eyed insight into the most dramatic moment of the modern history of the

West, the downfall of Napoleon, is really admirable, which I believe was made

possible only by his truly international perspective far beyond the realm of

Britain. And it was an expression of his political idealism conceived with

European mind, the kind of idealism Wordsworth had once had. What Byron wanted

to overcome through Harold's educational journey was a petty nationalism which

makes people blind not only to historical justice of a political event but also

to literary justice to the poets of universal and permanent fame. Byron

criticize vehemently the Florentines who, ignorant of the true value of Dante,

did not allow him to be buried in his own hometown with petty political

reasons.

Ungrateful

Florence! Dante sleeps afar,

Like Scipio, buried by the upbraiding shore:

Thy

factions, in their worse than civil war,

Proscribed the Bard whose name forevermore

Their children's children would in vain adore

With the remorse of ages; and the crown

Which Petrarch's laureate brow supremely wore,

Upon

a far and foreign soil had grown,

His Life, his Fame, his Grave, though rifled -not thine own.

(ll.

505-513. Stanza 57, Canto IV, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage)

The

reason why I have examined Wordsworth and Byron is to indicate that both works,

The Prelude and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, constituting the

canon of the great tradition of British Literature themselves, were made

possible only by their "external" point of view, or the

"otherness" to the British tradition. Their cosmopolitanism remained

more or less within the limit of European territory, but doesn't it strongly

suggest the real value of "externality" or "otherness" of

the viewpoint in reading history and culture? Self-awareness of our Asian

identity, recognition of our "otherness", aren't they give us a new

perspective with which to read their classic literature with fresh insights

otherwise unavailable? As Byron's perspective "external" to the

tradition of Italian literature enabled him to appreciate more clearly the

universal value of Dante, our own cultural context, so external to that of

Europe, may well be providing an advantageous viewpoint from which we could do

more justice to the real value of their literature. Perhaps such awareness is a

suitable first step to take to think about an anti-colonial

"translation" of their culture from a truly international

perspective.

9.

The "Utility" of Romantic Education: the Idea of Bildung I

have been trying to explain my thoughts on how Asian English Studies could make

sense making a distinctive contribution to the literary scholarship itself

whether it is in the center or periphery. It was mainly about the significance

of our research performed here in Asia. To be able to justify our profession of

university professors in relation to the geographic location of Asia, we should

think about our performances as teacher. What kind of teaching should we commit

ourselves, what "relevance" could we claim with our education of

English Literature here in Asia? Earlier I was talking about a little bit of

colonial past both of us have and our rather "awkward" place in which

we find ourselves in relation to that matter. Are we just "local

agents" voluntarily working for the colonial ideologues of the

Anglo-American world still alive and kicking? Perhaps the question itself would

be an unforgivable insult on our trade if it were given by somebody outside

Asia. But the question had always been hanging around within my mind for a long

time. My answer is of course, Definitely Not!

But what are we doing now? What have we been contributing precisely to

our communities? As far as Korea is concerned, I can say this. If we agree to

Martha Nessbaum's opinion that we need the humanities for democracy, not for

profit, we Korean scholars of English studies do have a lot of meaningful works

to do because there is still long way to go for Korea to reach the level of

Democracy United States or UK have. Yes, we have been making a progress and

been able to elect the president with a relatively democratic system since

1987. But democracy precisely up to that point. This is not a place for a

political speech, but I have to say this. Unless we have people enlightened

enough not to vote for the candidate who denies the cause of democracy

justifying the dictatorship for economic prosperity forgetting how much sacrifice

had been made to end that very dictatorship in less than three decades, the

democracy materialized in the election system is only of limited use.

Wordsworth

himself had the same feeling of disenchantment as mine when he exclaimed

“France was like a dog/ Returning to his vomit”(The Prelude, 1805, Book X, l. 935). Democracy depends on people and

the people should change, the people should get enlightened. The people should

learn that democracy is achieved only in proportion to the extent that they

realize the real value of Libery, Equality, and Fraternity . In this context, I think we could argue that

our teaching does have enormous amount of "utility": we could grow a

citizen embodying civic virtues necessary for democracy if not "a talent

making "an entry annual salary of two hundred thousand US dollars."

In this regard also, we have a lot to learn from the Romantic studies because

the idea of liberal education established in the 19th century originated from

the Romantics. It would be a long story if I follow properly the history of

liberal education in Britain (from Wordsworth, Newman, Mill, Arnold, and Leavis),

but I will briefly explain the concept of "Bildung" that I believe

lies beneath all the major literary projects of British Romanticism. Let me

start with a short description of "Bildung" from a book on the early

German romantics.

This

word(Bildung) signifies two processes--learning and personal growth--but

they are not understood apart from one another, as if education were only a

means to growth. Rather, learning is taken to be constitutive of personal

development, as part and parcel of how we become a human being in general and a

specific individual in particular. If we regard education as part of a general

process of self-realization--as the development of all one's

characteristic powers as a human being and as an individual--...they(the

romantics) insisted that self-realization is an end in itself...the very

purpose of existence. (The Romantic Imperative, Frederick C. Beiser,

pp.91-92)

"Bildung"

means literally "education," in German but what makes the

"Bildung" special is that it means a kind of "automatic"

education. Man learns by himself. Man learns not from the textbooks, not from

teacher, but from himself, but from an introspection into himself. How could we

learn by ourselves? That is because we have "the perfect man" already

within ourselves which are waiting to be realized in due course. Many people

think that Friedrich Schiller gave a classic expression to those thoughts in

his Aesthetic Letter.

It

may be urged that every individual man carries within himself, at least in his

adaptation and destination, a purely ideal man. The great problem of his

existence is to bring all the incessant changes of his outer life into

conformity with the unchanging unity of this ideal. (Aesthetic Letters

IV, Second Paragraph)

We

have the type of a perfect man installed within ourselves, and all we have to

do is to allow such a man realize itself naturally. Hence Rousseau who wanted

to leave the children to grow without any intervention of school education.

Hence Wordsworth who wanted us to throw away the books and go out to enjoy Nature.

But Schiller was not an advocate of "natural" education like Rousseau

or Wordsworth, but an advocate of "art" education. Schiller's

"art" comprises not only the fine art in the modern sense but also

poetry, drama, music, etc that are related to the development of human

sensibility. And this is the very origin of the idea of liberal education, the

education with special focus on the literary classics in the later development

in the 19th century Britain.

We also know that this was the foundational idea of Berlin University

created by Wilhelm Humboldt in 1810, although philosophy, not art, occupied a

central place in his curriculum of "Bildung." With this romantic

concept of "Bildung" in mind, we now come to understand why we have

so many stories of "growth of mind" in the poetic projects of

Romanticism. Apart from The Prelude and Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

we have already mentioned above, a story of “the growth of mind” is everywhere:

Wordsworth’s famous “Tintern Abbey, The young poet of The Ruined Cottage, The

wedding Guest of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, The Poet in Shelley's “Alastor,”

and many “Byronic” characters typically portrayed in Byron’s Don Juan. I believe that teaching and reading such

works which describe the growth of human mind, nurturing the human sensibility

is of enormous "utility" in the modern world as well. In the country

like Korea, which has to learn what civic virtues make a democratic country,

such a story of growth conceiving a dream of a perfect man in the West is an

education of great significance. Living as a professor of humanistic

disciplines like English Language and Literature in the age of transnational

capitalism, it is impossible not to fight against the barbaric logic of

Neoliberalism that threatens our work places in a fundamental way. Maybe it

might become a reiteration of the same old stories we heard again and again in

the last 100 years to argue against utilitarians with a romantic dream of

"Bildung,” but I believe that it is still useful and significant to remind

once again what John Stuart Mill recollected in his biography how he had come

to realize the importance of human sympathy through Wordsworth's poetry.

What

made Wordsworth's poems a medicine for my state of mind was that they

expressed, not outward beauty but states of feeling, and of thought coloured by

feeling, under the excitement of beauty. They seemed to be the very culture of

the feelings which was in quest of. By

their means I seemed to draw from source of inward joy, of sympathetic and

imaginative pleasure, which could be shared in by all human beings, which had

no connection with struggle or imperfection, but would be made richer by every

improvement in the physical or social condition of mankind. (John Stuart Mill,

John M. Robson and Jack Stillinger eds. Autobiography and Literary Essays.

University of Toronto Press, 1981. p.150.)

10.

Concluding Remarks

What

I have been trying to argue with this idea of Bildung as the key concept of Romantic Education is that we still

need them to grow our students into the World Citizens with civic virtue for

democracy. What Mill had learned from Wordsworth’s early nature poetry was the

sensibility of human sympathy, the ability to feel the pain of others’s as if

they were his own. Only such ability, “he could afford to suffer/ With those

whom he saw suffer”(The Excursion,

Book First, ll. 370-71). Such mental ability brings about an emotional

attachment to the community, the sense of fraternity which is the very

foundation of a democratic society.

I

have been trying to explain to you how to make a sense of Asian scholarship of

English Studies, how to make them more “relevant” to the community we live

in. The “otherness” our geographical

location conditioned us with could become an advantage, not a handicap as a

scholar of English. The romantic ideal of Bildung

might still be a valid justification of our trade in our region. Let me

conclude my little story of English Studies in Asia with a quotation from a

recent book “The Global Future of English Studies”(Wiley-Blackwell, 2012) by an

American scholar who is quite appropriately named “James English”. After his

statistically based analysis of the current states of English studies both in

and outside the Anglophone academia, professor English wants to draw a

conclusion by presenting a prospect rather more positive than those of authors

of “crisis” narratives.

The

future expansion of English studies will mostly occur outside the discipline’s

traditional Anglophone and European bas. We are approaching a turning point at

which, in strictly quantitative terms, the most consequential decisions about

what and how we teach will be made on the seeming peripheries of the

discipline. This represents an opportunity for all of us in the field to

unsettle the established pattern of time-lag emulation, whereby the literary

curriculum at a university in Seoul resembles that of a university in New York

30 years earlier. The tail of foreign variants is becoming long enough to wag

the dog of domestic English lit. The English departments in East Asia, only

just now beginning to test the water of Anglophone Asian literatures, could

have much to contribute to the future of that burgeoning field.

(English

191)

Although

I know that there is no more time-lag of 30 years in the curriculum of English

departments in Seoul, I want to share his optimism for the future of Global

English Studies indicating that there may be something else too that we could

contribute to this field other than the subject of Anglophone Asian

literatures.

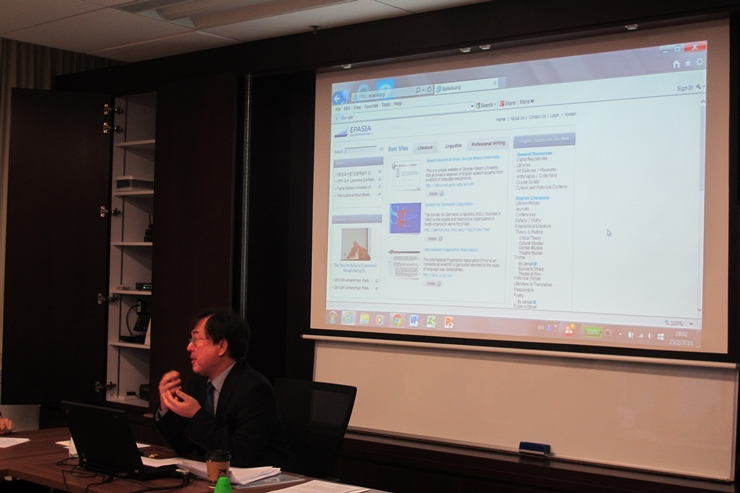

Coda:

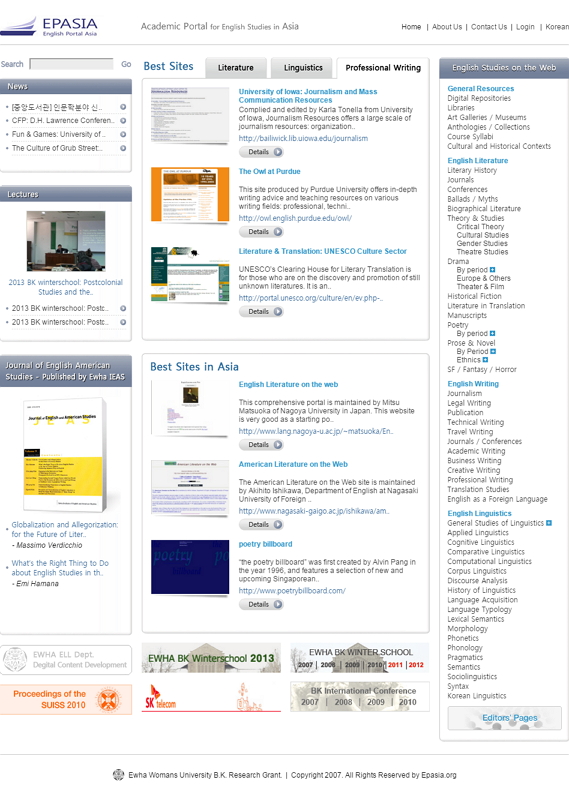

EPASIA(English Portal Asia)

Before

I finish my talk, I want to introduce an incomplete project which was created

by myself a few years ago to forge an academic community of English Scholars in

Asia making use of digital technology on the Web.

EPASIA(English

Portal Asia) was created back in 2006, being operated for a while and remain

incomplete from about 5-6 years ago. It is still working, but requires a

substantial update. Since we have recently selected for the next stage of Brain

Korea Project until 2020, we are thinking of revitalizing it with a little help

from our friends abroad who might be also interested in establishing a network

of academic collaboration in Asian region.

(I

have been working on Digital Humanities(formerly called Humanities Computing)

ever since 1999, having completed 6 different projects related to what is now

known as Digital Humanities. EPASIA is the peak of my digital commitments in

the last 15 years. EPASIA has the following characteristics.)

a. Global Scope:

EPASIA is an Academic Portal Site specialized in English Studies, which was, of

course, inspired by Alan Liu’s Voice of

the Shuttle. Whereas VOS is a comprehensive portal covering all subjects in

the humanities and social sciences, EPASIA is only for the English Studies.

What is unique about EPASIA, however, is its truly global scope; it covers not

only Anglo-American regions (UK, US, Australia) but also many Asian countries

such as China, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, the Philippines, India, and Korea. (So

far we have uploaded information about a little more than 700 sites for English

Studies collected from all over the world and we are hoping to increase our

number of items and the quality of our information with the collaboration of

our foreign partners. If they contribute contents produced in their native

regions perhaps after their own "translation," EPASIA can become a

truly unique collection of site information, which, I hope, will make the

hitherto-unknown Asian scholarship in English studies more visible to Western

academic communities.)

b. Collaborative

Networking: EPASIA is also an annotated Webliography (bibliography of academic

web contents). EPASIA’s annotations are given by an open-ended, bilateral

network of scholars and graduate students in Asia. (A site concerning Jean Rhys

maintained by professor Pin-chia Feng of Taiwan, for example, was annotated by

a graduate student of my department majoring in contemporary British fiction

who maintains her own website related to her major field. An annotator is asked

to contribute reviews of items in her major field to EPASIA in a standardized

format, just in the way an independent local TV production company provides a

national broadcasting system with its own programs.) The contents of EPASIA are

(thus) uploaded and maintained by a networked community of students and

scholars who best know the contents in their own professional fields.

c. Digital

Publishing & Archiving: EPASIA presents an international academic journal

of English Studies, published both as a peer-reviewed e-journal and as a paper

journal. Print or audio-visual materials produced through international

conferences, workshops, and lecture series are collected and archived in the

EPASIA database(, and some of them are already provided to the general public.

Digital mediations of local academic activities will also make Asian scholars a

more significant presence in Western academic communities. What we can do

with a digital project like EPASIA may seem at first to be little more than

Caliban’s clumsy challenge to Prospero. With a little bit more solidarity and

positive participation among us, however, we may achieve something far more

constructive than Caliban’s curse.)

For more

details, you can refer to the leaflets I prepared or you can visit the site

epasia.org yourself.

This is it for

today, and thank you very much for your listening. Thanks a lot.

|