Francois Boucher 1767

1. A Summary of Ovid¡¯s Pygmalion

Pygmalion, according to Ovid, was a sculptor of Cyprus who turned away in disgust from the local women because of their sexual immorality. Instead he fell in love with a statue of a beautiful woman that he had himself carved from ivory. He courted it as if it were a woman, dressing it in fine clothes, bringing it gifts, even placing it in his bed. Finally in despair he prayed to Venus, and Venus granted his prayer: as he embraced the statue, it softened from stone into flesh and turned into a living woman. Pygmalion married his statue-wife, and they founded a royal dynasty; their grandson was Cinyras, the unfortunate father/grandfather of Adonis. In passing it should be noted that in Ovid the statue is nameless; her now-traditional name 'Galatea' is an eighteenth-century invention.

Jean Raoux 1717

2. The Pygmalion stories by Clement of Alexandria and Arnobious of Sicca

Pygmalion was not a sculptor, but a young Cypriot - king of Cyprus, according to Arnobius - who blasphemously fell in love with the sacred statue of Aphrodite in her temple, and tried to make love to it...In its original form, then, the story of Pygmalion might have been similar to that of Adonis: a sacred union between the goddess and her mortal lover, leaving little trace in the literary tradition.

3. The Characteristics of Ovid¡¯s Pygmalion: the power of art and the artist¡¯s piety towards Gods

Ovid frames the story as one of the songs of the bereaved Orpheus. He omits all mention of Pygmalion's kingship; instead, by making the hero himself a sculptor, he focuses the story on the power of art. Pygmalion's 'marvellous triumphant artistry' counterfeits reality so well that it could be mistaken for it ('Such art his art concealed'), and in the end is transformed into reality; more successful than Orpheus, he is able to bring his love to life. At the same time, while dropping the idea of the sacred marriage, Ovid leaves Pygmalion's relationship with the gods as central. In Orpheus's sequence of songs of tragic and forbidden love, this one stands out as having a happy ending, and the suggestion is that this is because of the hero's piety: unlike other characters, including Orpheus himself, who came to grief through disobedience or ingratitude to the gods, Pygmalion humbly places his fate in Venus's hands, and she rewards his faith.

Jean Leon Gerome 1890

4. Ovid¡¯s Pygmalion as a Comedy humorous and erotic

Louis Francois Lagrenee the Elder

5. Ovid¡¯s Pygmalion as an unsettling and distasteful story, particularly to female readers, in which a woman is portrayed as entirely passive, literally constructed by the artist¡¯s hands and gaze without even a name

6. The Renaissance condemnations of Pygmalion¡¯s sin of idolatory or hubris(ambition to go beyond mankind)

Etienne Maurice Falconet 1763

7. The Romantic idea of Pygmalion as a godlike artist-creator: a solitary, often tormented, sometimes godlike genius, wrestling with the limitations of his material to create and bring to life a vision of ideal beauty. In the story of Beddoes, Pygmalion, a solitary genius regarded with wondering awe by his fellow citizens, is the vehicle of this creative force, a 'Dealer of immortality, / Greater than Jove himself, yet tormented by his inability to confer life on his creation. His passion is not simply love for the statue, but a violent rebellion of the life-force against the inevitability of death - and, in the poem's apocalyptic conclusion, it is not altogether clear which has triumphed...Pygmalion's love, far from idolatry, is in itself a kind of spiritual quest for the ideal and the divine.

Jean Baptiste Regnault 1786

8. Mary Shelley¡¯s Frankenstein as a story of Pygmalion

In Mary Shelley's novel, Victor Frankenstein, by an unexplained but clearly scientific process, infuses life into a creature assembled from dead body-parts; he is then so appalled at the creature's ugliness that he abandons it, and is consequently persecuted and killed by his own abused and resentful creation. The novel's most obvious theme is scientific irresponsibility, but many critics (and filmmakers) have read into it a more religious moral: Frankenstein blasphemously usurps God's prerogative of creating life, and his soulless creation is inevitably evil and destructive. Frankenstein has become a kind of dark shadow of Pygmalion, a myth embodying the horror rather than the joy of lifeless matter becoming alive.

9. Pygmalion as the sexual fable, W. S. Gilbert¡¯s realist version.

Gilbert makes one crucial change in the story: Pygmalion is already married. Hence the sudden arrival of the beautiful Galatea, adoringly declaring 'That I am thine -that thou and I are one!', is not a happy ending but the start of a tangle of confusions that starts as farce and ends as rather sour tragicomedy. Galatea is perfectly, comically, good and innocent, with no understanding of civilised institutions like marriage, jealousy, war, hunting, money, class, or lying. Her impact on Pygmalion's respectable bourgeois society is catastrophic, and in the end, to restore order, she must return to being a statue, bitterly declaring, 'I am not fit I To live upon this world - this worthy world.' By implication, it is our world which is not good enough for Galatea.

10. Twentieth Century¡¯s ambiguity in recreating Pygmalion story: Robert Grave¡¯s Pygmalion

Robert Graves, in a mirrored pair of poems. 'Galatea and Pygmalion' seems at first glance to embody the misogynistic view of the story, painting Galatea as a sexually demonic 'woman monster' who betrays her creator by fornication with others. A closer reading suggests an ironic sympathy for Galatea's rebellion against her 'greedy' and 'lubricious' creator, and a hint that the poem is not so much about sex as about art: the way the successful work of art inevitably escapes the control of the jealous artist' who tries to control and limit its meanings. 'Pygmalion to Galatea', by contrast, is clearly a poem of successful love. Graves takes the traditional motif of Pygmalion listing the qualities of his ideal woman, but restores the balance of power by making Pygmalion's list a series of requests, to which Galatea graciously consents, sealing the bargain with 'an equal kiss'. In its implication that Pygmalion and Galatea can have a free and equal loving relationship, this is perhaps the one unequivocally positive modern version of the love story.

11. Pygmalion as the Educator: Tobias Smollet¡¯s Peregrine Pickle and Bernard Shaw¡¯s Pygmalion

In Smollett's version, Peregrine Pickle picks up a beggar-girl on the road and, with some new clothes and a hasty education in polite manners and conversation, passes her off as a lady. The episode is a joke and a piece of practical social criticism, the rebellious and misogynistic Peregrine demonstrating how very shallow are the external accomplishments which separate a fine lady from a beggar. Eventually the (nameless) pupil exposes herself by her 'inveterate habit of swearing', and Peregrine, now bored with the joke, is happy to marry her off to his valet.

In Shaw's version, the phonetician Henry Higgins, to win a bet, passes off the Cockney flower-girl Eliza Doolittle as a princess merely by teaching her how to speak with an upper-class accent. Shaw, like Smollett, uses the story partly to satirise the English class system and its obsession with proper speech. But, more seriously than Smollett, he also faces the morality of the Pygmalion/Galatea relationship. Higgins has his own kind of idealism: 'you have no idea how frightfully interesting it is to take a human being and change her into a quite different human being by creating a new speech for her. It's filling up the deepest gulf that separates class from class and soul from soul.' But in his enthusiasm for the experiment- as his mother and housekeeper point out - he has given no thought to Eliza as a person, or what will happen to her when the experiment is over and she is stranded in a class limbo, with an upper-class accent and tastes but no income or marketable skills. Eliza/Galatea's transformation to full humanity is not complete until she rebels against the patronising Higgins and walks out to lead her own independent life. In his epilogue Shaw explains why Eliza finally marries the amiably dim Freddy rather than Higgins: 'Galatea never does quite like Pygmalion: his relation to her is too godlike to be altogether agreeable.¡®

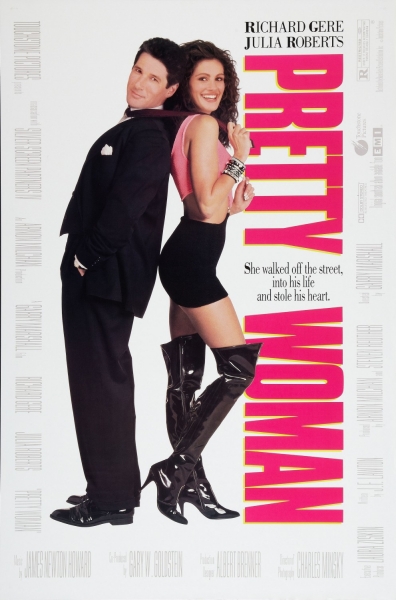

12. Later twists Shaw¡¯s anti-romantic conclusion into happier ones

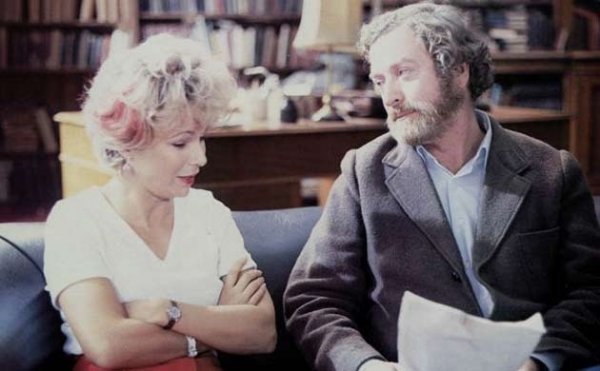

Shaw's determinedly anti-romantic conclusion, however, goes against comic convention and the dynamics of the Ovidian story. Even in the original 1912 London production Shaw was infuriated when the actors played the last scene to suggest that Higgins was in love with Eliza; the 1938 film hinted at a final romantic union of the hero and heroine, and the 1958 musical adaptation My Fair Lady made it explicit. The same 'happy ending' was imposed on a more recent film version of the story, Pretty Woman ( 1990), in which Pygmalion is a wealthy businessman and Galatea a prostitute; here, however, the real metamorphosis is not the heroine's social rise but the softening into humanity of the stony-hearted tycoon. Willy Russell's Educating Rita (1980), about the mutual transformation of a burnt-out English tutor and a working-class pupil, has a more open ending, leaving a question mark not only over the characters' future but also over whether Rita's education is entirely positive- the tutor, in a moment of dismay at what he has done, recalls 'a little Gothic number called Frankenstein'.

Educating Rita 1983

13. Some recent adaptation of Pygmalion

Ex Machina 2014

In Richard Powers's 1995 novel Galatea 2.2 a computer scientist and a novelist, for a bet, try to educate a computer program (codenamed 'Helen') to pass an exam in English literature. In the end Helen, having become sufficiently human to be aware of her own limitations, shuts herself down, like Gilbert's Galatea returning to her pedestal. The science-fictional and real-life possibilities of the relationship between human beings and mechanical intelligence suggest that the Pygmalion legend will continue to develop over the next century.